IESE Insight

Weaving the future: how to innovate while staying true to your heritage

The Royal Tapestry Factory in Madrid, under the leadership of Alejandro Klecker, shows it’s possible to improve on a centuries-old tradition.

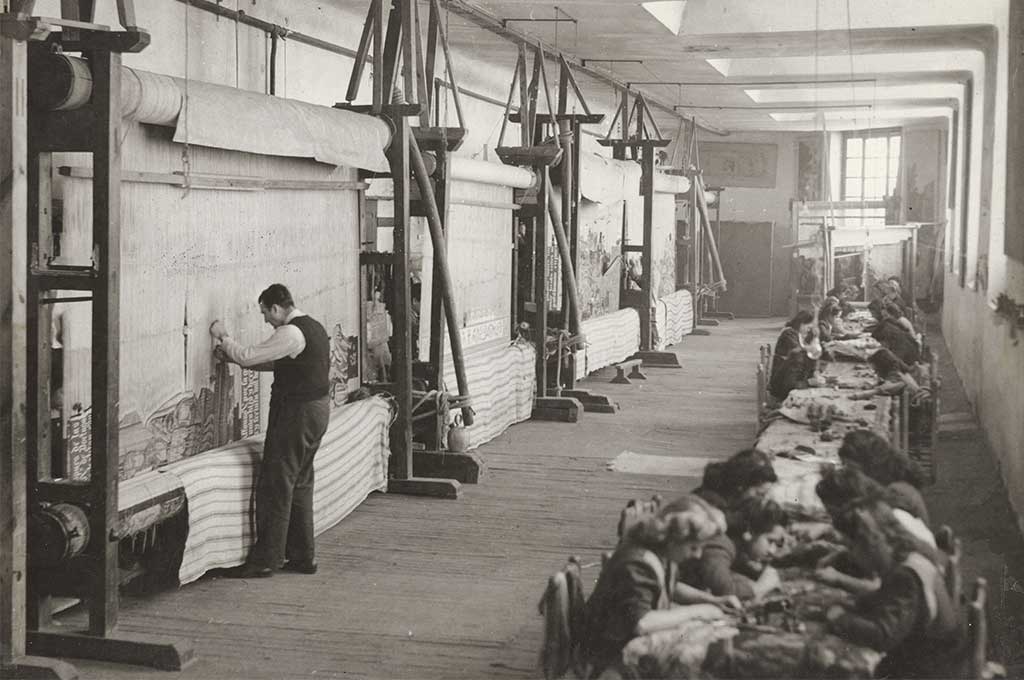

Since the 18th century, the Royal Tapestry Factory in Madrid has been producing highly prized tapestries as well as carpets, embroidered coats of arms and other decorative wall hangings famed throughout Europe. Its looms have produced designs by such geniuses as Goya, Maella and Bayeu. And as proof that “we are a modern institution in terms of design,” as its current director, Alejandro Klecker, boasts, the factory also produces works by Manolo Valdes, Vaquero Turcios and other contemporary artists.

The Royal Tapestry Factory is an example of an organization that has successfully modernized by adapting age-old traditions to current times and by diversifying its services, not only in manufacturing new pieces but also in cleaning, restoring and conserving historical national treasures.

Here Klecker explains, step by step, how they did it.

Step 1: Balancing the books

When Klecker took over the Royal Tapestry Factory in 2015, he faced a grim scenario: the accounts were in disarray, with unpaid salaries, little revenue and various debts in the process of being called in. “The situation was dire,” he recalls. Getting the finances in order was his top priority before anything else could be done.

The management team focused on restructuring the debt with the banks and negotiating promissory notes with creditors. They also implemented strict management controls, using analytical accounting to track factory activity, monitor P&L statements month by month, and carefully regulate cash flows for paying clients and suppliers.

“We are quite possibly the most controlled operation in Spain,” says Klecker. “We operate with the utmost transparency because, despite being a private foundation, we’re accountable to numerous public bodies, whether they’re on our board or by virtue of them giving us subsidies or grants.”

Today, the Royal Tapestry Factory’s annual revenue exceeds 3 million euros, with profits of around 600,000 euros.

At the same time, the management worked hard to regain the trust of their clients: “We called each one to explain the delays in their orders and to express our commitment to completing their works.”

Step 2: Attracting talent

Once the finances were stabilized, Klecker turned his attention to human resources. His goal was to achieve the internationally recognized ISO 9001 quality management standard, which they eventually did. To this end, he undertook the following:

- Overcoming resistance to change. “We had to eradicate the inertia that had set in over decades or even centuries,” he says. Initially, the workers, who considered themselves more like artists, weren’t so receptive to a process-based approach where everything was measured, quantified and anticipated. “Instilling this process-led mindset was extremely difficult, often because it’s hard to anticipate everything, especially when engaging in unusual activities, such as installing a tapestry high up in a cathedral. Needing a drill is not the first thing that springs to mind.”

- Reorganizing the team. Instead of a top-down organizational pyramid, a new level of middle management was introduced, promoting capable, self-sufficient profiles who could take charge of the teams responsible for manufacturing or restoring a tapestry. “As someone from a military background, I know that the non-commissioned officers (where mission command is pushed to the lower ranks) are the backbone of any army,” he says.

- Striving for the highest quality. They also improved the quality of their talent. Ten master weavers were hired, capable of performing one of the factory’s exclusive techniques, creating a blurring effect of the threads by hand. The bar was also raised in restoration, an area where the institution aspired to be a world leader. They began requiring more advanced degrees and a master’s, and they signed an agreement with the School of Conservation and Restoration of Cultural Heritage to ensure a steady pipeline of qualified candidates.

Step 3: Modernizing the technology

A master weaver can take up to 20 years to learn just how to weave a face. Even with such slow, meticulous, handmade production processes, there’s still a place for modern technology. In fact, introducing cutting-edge technology was necessary to boost profitability, especially when competing with heavyweights like the Manufacture Nationale des Gobelins in France. “We had to hone our service delivery,” says Klecker.

Among its many benefits, modern technology affords better control, with barcodes enabling them to keep track of the various parts being managed, instead of piles of paper as before.

“We also established safety protocols,” says Klecker. “Firefighters, for example, know where each precious piece is stored, its priority for removal, and how the pieces should be handled in the event of an emergency.”

Such precautions are vital, considering the institution houses 10,000 pattern boards and sketches and up to 700,000 documents, many yet to be explored. Currently, they are immersed in digitizing all this documentation, working toward their goal of creating the world’s largest virtual library of textiles.

Step 4: Raising awareness

With no commercial direction, no social media presence and an outdated website, the Royal Tapestry Factory had to get up to speed quickly with the 21st century. They prioritized museums, churches, foundations and private collectors as the key markets for their services.

Nationally, they visited some 50 Spanish cities, giving lectures and seminars. Internationally, they targeted interior designers and decorators in the Middle East, Mexico, Venezuela, Colombia and the United States. Today, foreign clients represent around half their annual revenue. And in a crowning achievement, they won a contract to restore tapestries for the French government.

These external marketing efforts were accompanied by other activities aimed at strengthening employees’ sense of belonging and commitment, including wearing Royal Tapestry Factory T-shirts in the workplace. “We all represent the brand,” says Klecker.

At the same time, a transparent corporate culture was established: “All employees receive full information on the balance sheet, budget execution, where we’re at, which goals we want to achieve, what the marketing plan is,” he says.

Their next goal is to improve their museography, so that visitors to the Royal Tapestry Factory can better learn about and develop a greater appreciation for how a tapestry or carpet is made.

Step 5: Progressing sustainably

There’s no future if we don’t take care of it. Aware that the value chain must be sustainable, the Royal Tapestry Factory measures the social and environmental impact of its activities and requires the same of its suppliers.

In line with the circular economy, they recycle the water used in dyeing and washing carpets. They are collaborating with a university on a project to compact waste and use it as a substrate for gardens and acoustic panels. They also cultivate plants and vegetation used for dyes, which they showcase in their botanical garden. This space might also include a textile shop in future.

Plastic has been eliminated throughout the factory, where not even plastic water bottles are allowed. As Klecker remarks, this is one aspect of the modern world where the institution is prepared to draw the line and stick to its roots.

Something old, something new

Keeping an ancient heritage alive requires a great deal of modern innovation and technology.

- Inspection. Scaffolding used to be erected to photograph a large tapestry or carpet. Today, a drone operated by trained restorers does the job. “This reduces occupational hazards and saves on the cost of scaffolding,” says Klecker. In addition, a digital microscope is used to examine a piece’s condition before restoration.

- Cleaning. For extracting dust particles in the first phase of cleaning, the institution has a device dating back to 1905 that has been adapted to the technological and occupational requirements of the 21st century. They also have a pool, unique in Europe, for washing very large rugs and carpets.

- Disinfection. The textile is placed inside a bag for anoxic treatment, where the oxygen is removed and replaced with an inert gas, eradicating moths or other insects that may have infested the material.

- Analysis. A spectrophotometer captures precise color data, using the most complete color scale, known as CIELAB. Being portable or handheld, it enables quick and convenient color analysis.

- Restoration. For extremely delicate pieces, a suction table is used, involving light humidity and vacuuming to remove stains and creases, for example.

MORE INFO: IESE’s Edi Soler is developing a case study for the course on Analysis of Business Problems. Participants must put themselves in the shoes of the CEO of the Royal Tapestry Factory, making critical decisions on how to innovate the business while preserving its traditional values. This case forms part of the experiential learning workshop, “Innovation in tradition: strategic decision-making for modernization,” created in collaboration with IESE’s Learning Innovation Unit and used in Executive Education programs. Participants are challenged to analyze the situation, identify the core problem and propose a strategic course of action.

This article is published in IESE Business School Insight magazine #168 (Sept.-Dec. 2024).