IESE Insight

How profitable are bike-sharing systems?

For every 1 euro invested in urban bike-sharing programs, cities are seeing as much as 1.72 euros in return. Will this golden era of cycling last? A look at the economics, well-being and future directions on two wheels.

In some European cities, it's passé to own a bicycle. The preferred way of getting around town may still be on two wheels, but the bikes are likely to belong to a public bike-sharing system.

Pioneers of the idea from the mid '60s would be amazed. Although there had been various attempts to launch bike-sharing programs throughout the 20th century, it wasn't until the "third wave" of bike sharing, in the late 1990s, that the concept really took off. Since then, bike-share programs have spread throughout cities, principally in Europe, but also in North America and Asia. They are usually run publicly or via public-private partnerships (PPPs).

But do they pay for themselves?

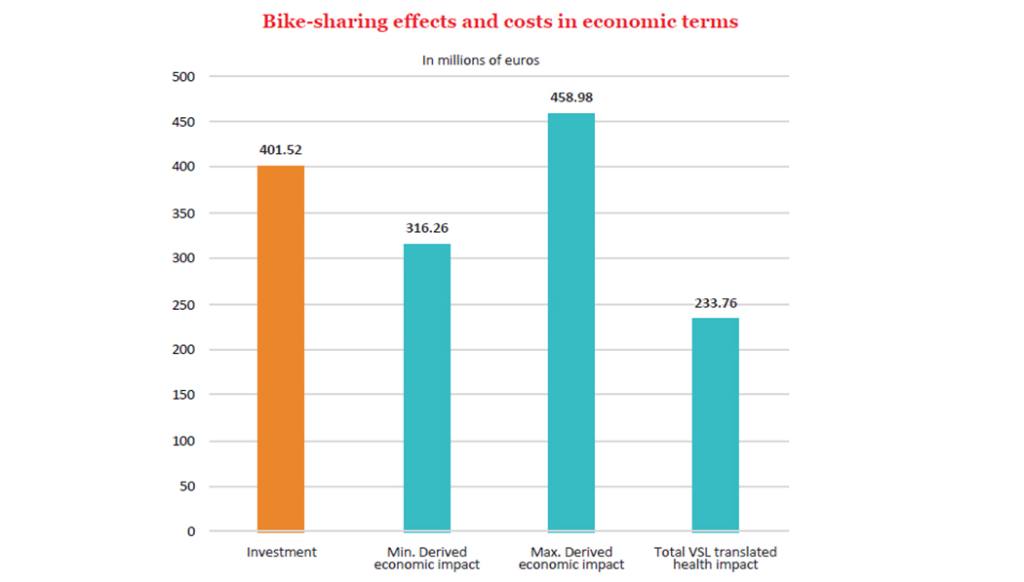

They do, to the tune of 1.37 to 1.72 euros of value per 1 euro spent, according to a report by Joan Enric Ricart with Miquel Rodríguez Planas of IESE's Specialist Center on PPPs in Smart & Sustainable Cities (PPP for Cities), together with Sergi Martínez, Albert Tapia and Valeria Bernardo. The report examines both the economic performance of 13 bike-sharing initiatives in Europe, and new potential challenges arriving on the scene.

These numbers were arrived at by evaluating both the direct economic impact of the bicycle programs, in terms of job creation, revenues and knock-on economic effects on local businesses, and in terms of the health benefits derived from increasing physical activity and shifting traffic patterns.

On the economic side, the analysis considers job creation, effects in related industries and increased demand in households benefitting from job creation. On the public health side, the traffic mortality risk and increased exposure to air pollution that cyclists face is discounted from the positive health outcomes that cycling brings.

The authors studied these effects on bike-share programs in 13 European cities, all national or regional capitals — Barcelona, Berlin, Bilbao, Cologne, Copenhagen, Hamburg, London, Madrid, Milan, Paris, San Sebastian, Turin and Vienna.

When measuring economic impact alone, it was ambiguous whether or not bike-share programs paid for themselves: the economic impact in the 13 cities studied was between 0.79 and 1.14 euros per euro spent.

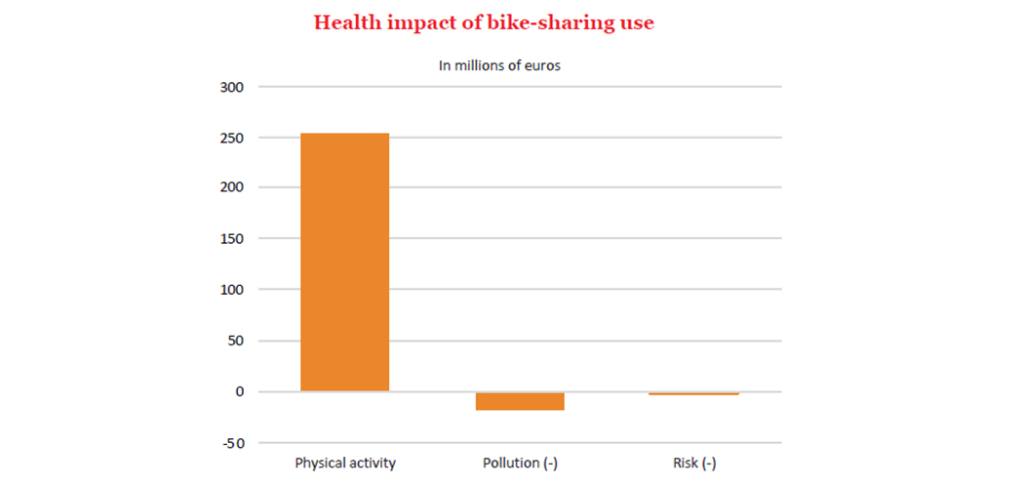

The health benefits tipped the balance, however. Although there are dangers associated with increased bicycle use (accidents, inhaling more polluted air), these are, the authors state, "far from eclipsing the health benefits obtained thanks to the physical activity that bike-sharing systems allow." Overall, the health benefits were the equivalent of preventing more than 90 premature deaths in the 13 cities between 2014 and 2016, representing 0.12 percent of estimated deaths of people under the age of 65 in those cities. There were corresponding savings in the health-care systems.

Once both direct economic impact and positive health outcomes are combined, the programs are shown to exceed in value what they cost in implementation.

In this graph, the program investment is presented in orange. Estimates of the positive externalities generated by the 13 bike-sharing systems analyzed are then presented in blue. Note that VSL (value of statistical life) is an estimate of how much people are willing to pay to lower risks to their lives. (This chart applies the average European value of 2.5 million euros

per life.)

Bike sharing 3.0 — to 4.0

So, third generation bicycle programs seem to be worth the money. But in the ever-changing innovation landscape, nothing remains constant for long, and the model itself is being threatened by a new arrival: "dockless" bike-sharing systems.

When not in use, most third-generation bikes are parked at docking stations, where they lock automatically until the next user comes to access them. But the new dockless model takes advantage of the age of the smartphone to allow bicycles to be left anywhere. Unlocking it with an app, users pick up the bike closest to them and leave it wherever their journey ends.

These dockless programs have some competitive advantages (no docking stations, potentially more convenient for users) and disadvantages (increasingly complex logistics for redistribution, reliability issues, a higher chance of being coopted for private use, and finally, questions surrounding the financial sustainability of the business model itself). The dockless systems' future is still unfolding. Most importantly, as largely private initiatives, they may challenge the public, institutionalized systems.

The threats include direct competition, which could undermine the economic viability of the public programs; the possible abuse of public space; and the problem of maintaining the new bicycles sufficiently to avoid injuries. Some cities have already begun to propose frameworks of use and specific parking areas for dockless bicycles. More regulation may be necessary in the future.

It's clear that with more than half the global population living in cities and a continuing trend against car ownership among young people, as well as positive economic returns and health benefits, bicycles are here to stay. For the best results, a harmony between institutionalized models and innovative new ideas will have to be found.

Methodology, very briefly

The economic effects of the 13 bike-sharing programs were measured by applying Leontief input-output matrices to assess the economic activity of each bike-sharing project on a country level. The health outcomes were computed using the HEAT tool provided by the World Health Organization, which also provided the monetary value of avoided premature deaths using estimations of the value of statistical life (VSL) presented by the OECD.