IESE Insight

Discovering what makes your employees tick: the role of culture on motivation and behavior

For better management and employee productivity, consider the role of culture. Especially for global organizations, appreciating cultural differences is vital for success.

By Carlos J. Sanchez-Runde and Richard M. Steers

We’ve seen it time and again: An organization faces financial pressures and needs to cut costs. What should it do?

- In the United States, the solution usually involves layoffs. While widely recognized as causing personal hardship, layoffs are often deemed a prudent response by U.S. managers.

- In the Netherlands, however, labor laws make downsizing staff more difficult and more costly, so Dutch firms will often seek other remedies, such as employee buyouts.

- In Japan, managers would be loath to make layoffs; the loss of reputation this would incur would put their business and future hiring opportunities at risk. Instead, Japanese managers prefer to transfer redundant employees to other parts of the organization or to subsidiaries.

Financial difficulties occur everywhere, but the same problem leads to three very different solutions, depending on the various cultural drivers at play. In this and many other areas, culture strongly impacts work behaviors.

However, serious study of the relationship between culture and behavior is difficult. Things get lost in translation, intercultural sensitivities impose self-censorship on dialogue and debate, and everything takes more time and costs more money than originally planned.

Even so, this does not excuse or justify ignoring what is clearly one of the most important variables in the study of human behavior in organizations today: culture.

Fortunately, cultural perspectives as they relate to employee motivation and work behavior are increasingly being addressed. Recent empirical studies have demonstrated that cultural variations can have a significant influence on work values, equity perceptions, motivational achievement, job attitudes, and many other areas.

Still, the concept of culture as it relates to organizational dynamics remains fuzzy. While people may be willing to accept that managers in different countries behave differently when confronting the same challenge, managers must recognize that this is only the beginning of the journey toward understanding social dynamics in the workplace.

This article will review our current understanding of the relationship between culture and work motivation in order to explore the implications for managing and motivating employees around the world.

The role of management across borders

Before talking about motivating workers, we first need to qualify the nature of management and the significant role that cultural differences can play in both the conceptualization and practice of management around the world.

Definitions of management abound, but from the 19th century through to the present, most writers have agreed that management involves the coordination and control of people, materials and processes to achieve specific organizational objectives as efficiently and effectively as possible.

One idea holds fast: organizations must be managed through strength and logic. This conception of management sees the managerial role as being one and the same across time and space.

Indeed, Henry Mintzberg concluded that all managers’ jobs are remarkably alike, and that all managers serve 10 basic roles:

- figurehead

- leader

- liaison

- monitor

- disseminator

- spokesperson

- entrepreneur

- disturbance handler

- resource allocator

- negotiator

These traits, in turn, can be organized into three clusters:

- An interpersonal role, focused on building and leading effective groups and organizations.

- An informational role, focused on collecting, organizing and disseminating relevant information.

- A decisional role, focused on making and securing support for creative, strategic and tactical decisions.

Although the definition of management has remained fairly consistent over time, managerial practice differs significantly across cultures. For example:

- Malaysians expect their managers to behave in a manner that is humble, modest and dignified.

- Iranians seek power and strength in their managers.

- The French expect their managers to be cultured.

- Nigerians expect managers to duplicate the social patterns also found at social and even tribal levels in their organizations.

- Peruvian employees look for decisiveness and authority in their managers, even to the point of resisting attempts at introducing employee participation schemes.

- Some Americans like leaders who empower their subordinates, while others prefer leaders who are bold, forceful, confident and risk-oriented.

- The Dutch tend to emphasize egalitarianism and are skeptical about the value of a manager.

Mintzberg’s model can be useful in exploring, on a conceptual level, how culture and managerial roles can intersect.

- For example, considerable research has indicated that most people in individualistic cultures prefer managers who take charge, while most people in collectivistic cultures prefer managers who are more consultative.

- Similarly, managers in high-context cultures frequently make extensive use of the context surrounding a message to get their point across, while managers in low-context cultures tend to rely on specific and detailed messages and ignore much of the message context.

In short, the managerial role keeps changing — not necessarily in major ways, but certainly in important ways — as we move across borders.

Strategy and structure: not every culture sees them the same

Culture strongly affects how managers and managerial action interact with several of the more macro aspects of organizations, including their mission, values, strategy and goals, as well as their structure.

Historically, these relationships have been seen largely in terms of a one-way, causal relationship: mission determines strategy, which, in turn, determines structure, which governs management practice, which ultimately determines the extent to which the organization succeeds in achieving its mission.

More recent evidence, however, suggests a far more complex and interactive relationship. Specifically, while mission and values may help determine an organization’s initial strategy and goals, organizational design and even management practices can also influence strategy in significant ways. Likewise, strategy can influence structure, but so, too, can management practices.

These interactive relationships are played out in a business environment that is itself multifaceted and interactive. This includes such external factors as geographic location; the cultural milieu in which organizations work; legal conventions and local customs; variations in political and institutional support; a country or region’s endowments; the specific sector of the economy where the organization does business; available investments, technologies and markets; and environmental challenges and goals.

In other words, the simple strategy-structure-management paradigm is found to be sorely lacking in explanatory power as organizational theory crosses borders.

Not surprisingly, a company’s stakeholders can also have a major influence on both the determination of the company’s mission and its strategy. What is often overlooked is the fact that the nature and power of a stakeholder group can be influenced by the predominant culture in which the enterprise does business. We refer to this as the difference between a centralized and a distributed stakeholder model. For example:

- Some companies routinely face a stakeholder group where power and influence are centralized. In Korea, Mexico, the United Kingdom and the United States, investors, customers and governments often have considerable influence over enterprise mission and strategy, while employees and the public at large do not.

- In Germany, Japan and Sweden, the opposite situation often exists. That is, investors, customers and governments sometimes have a major influence over missions and strategies; but so, too, do employees and the public at large. American or British firms that are doing business in Sweden or Germany, therefore, must accommodate these different constituencies.

To accommodate these and other differences, global managers must first create a specific, realistic and clearly understood mission for a global enterprise. They need to articulate precisely what strategies will be employed in support of this mission.

This may require that they organize or reorganize the available human, physical and financial resources, and link them to appropriate management systems, in order to maximize the collective efforts directed toward strategic goal attainment.

Once operations have begun, managers should apply various control mechanisms to ensure that the organization remains on track.

Most strategy scholars suggest that there is a rational sequence between strategy and structure, in which the former precedes the latter. Hence, a “rational” company first determines its overall goals and objectives, and then designs or redesigns its organizational structure to support the strategy.

Unfortunately, while this practice may be common in the West, it is less common in other parts of the world, where local considerations often come into play. That is, the strategy-structure relationship is culture-bound to a certain degree.

Personal work values, work motivation and job attitudes

If we accept that the managerial role and the handling of strategic planning keep changing as we move across borders, then the same applies for workers themselves. We can examine this idea by exploring three areas: personal work values, work motivation and job attitudes.

1. Personal work values

Japanese workers are notorious for their strong commitment to work. They work long hours, rarely take their full allotment of vacation days and spend many post-work hours in the company of their colleagues. For the Japanese, work is their central life interest, in comparison with Americans and Germans, who place a higher value on leisure and social interaction. A high proportion of Americans see work as a duty and an obligation. Their personal work values differ significantly.

Values identify those aspects in life and work that people should focus on, as well as goals they should reach. Applied to work settings, personal work values represent a set of standards and goals to which people aspire and that have meaning to them on the job; they influence employee willingness and preparedness to contribute toward the attainment of organizational goals.

Adding a cross-cultural perspective raises questions concerning how variations across cultures may affect employee attitudes and behavior in the workplace, as well as what managers might do to accommodate such variations.

For example, values concerning the relative importance of individualism vs. collectivism can influence the manner in which employees are willing to work together.

Available research on culture and personal values consistently demonstrates a strong and significant relationship with work behavior. This appears to be true regardless of whether Western or non-Western templates are used for either conceptualization or empirical research.

As a result, it seems highly advisable to include the role of cultural differences in any future modeling efforts, as well as any managerial actions, that involve one’s self-concept, individual beliefs and values, and individual traits and aspiration levels.

These individual factors, in turn, have been shown to be closely related to self-efficacy, work norms and values, and ultimately work motivation.

2. Work motivation

Let’s look again at those American and German workers, for whom work is an obligation rather than a central life interest. What motivates them?

In the case of American workers, obtaining good health insurance is a strong motivation for obtaining and holding a job. The satisfaction of meeting established goals serves as motivation as well.

Countless factors motivate employees, but one thing is certain: culture determines what factors come into play in individual workplaces, and wise managers know that getting the most out of their workers requires understanding, targeting and leveraging the motivators that most affect their workforce.

Work motivation can be defined as that which energizes, directs and sustains employee behavior in the workplace. In other words, the concept of work motivation focuses on those aspects of both the individual and the situation that:

- cause initial willingness to exert energy and effort.

- direct this energy in one direction or another.

- sustain that effort over time.

While personal beliefs and values are clearly one determinant of work motivation, the following factors also contribute, where culture again plays a role.

Individual strengths. Murray believed that individuals are motivated by two dozen needs that become manifest or latent depending upon circumstances.

By contrast, Maslow suggested that individual needs are pursued in a sequential or hierarchical fashion, from basic needs (physiological, safety and belonging) to growth needs (self-esteem and self-actualization).

Yet neither Maslow’s “hierarchy of needs” nor Murray’s model is universally applicable across cultures.

Similarly, according to McClelland, as individual achievement levels rise within a nation, so, too, does the extent of entrepreneurial behavior and economic development. But it differs across cultures, as Krus and Rysberg found in their study of entrepreneurs from highly diverse cultures.

Cognitions, goals and perceived equity. Besides individual needs, work motivation can also be examined from a cognitive perspective by applying equity theory and goal-setting theory, both of which assume that people make reasoned choices about their behaviors, and that these choices influence, and are influenced by, job-related outcomes and work attitudes.

Equity theory focuses on the motivational consequences that result when people believe they are being treated either fairly or unfairly in terms of their rewards and outcomes — a belief determined by perception rather than objective reality. Research suggests that the equity principle may be somewhat culture-bound. For example, workers in Asia and the Middle East apparently readily accept a clearly recognizable state of inequity in order to preserve their view of societal harmony.

Goal-setting models focus on how individuals respond to the existence of specific goals, as well as how such goals are determined. Expectancy theory postulates that motivation is influenced by a combination of one’s belief that effort will lead to performance and that performance will lead to certain outcomes, whose value is determined by the individual.

Incentives, rewards and reinforcement. Incentives are perhaps the most influential factor in work motivation, involving:

- self-efficacy

- reward preferences

- merit pay

- uncertainty, risk and control

- compensation

All of these vary across cultures. Reward preferences, in particular, vary widely. Some cultures emphasize security, while others emphasize harmony, individual status or respect.

Attempting to integrate one culture’s incentive system into another culture’s often leads to failure. For example, efforts to introduce Western-style merit pay systems in Japan have frequently led to an increase in overall labor costs.

Social norms and belief structures governing levels of required effort. It goes without saying that social norms, which play a significant role in determining worker motivation, differ vastly across cultures.

Social loafing or free riding, for example, only work in contexts where the lack of individual effort can be hidden behind group behavior.

One additional key point is the differing levels of the importance of work and leisure in various cultures. It is often said that people in some societies work to live, while others live to work.

Some European countries have a 35-hour work week as standard, while the norm in the United States is closer to 50. The unanswered question is whether working harder than anyone else is a badge of honor, a sign of necessity or, worse, some deep psychological dysfunction. At a certain point, one study concluded, there is a negative rate of return on productivity resulting from working too long.

While perhaps overly simplistic, the work vs. leisure conundrum provides an easy conceptual entry into cultural differences, especially as they relate to the world of work.

However, this debate is only part of a larger debate over the social and economic consequences of increasing globalization. Many people believe — correctly or incorrectly — that globalization and the competitive intensity of the global economy are changing how people live in ways not imagined earlier. The open question is whether these changes are for the better or for the worse.

How can we make sense out of these various findings concerning the role of culture in work motivation? And what implications can be identified for global managers?

We can look at how cultural drivers create both opportunities and constraints on efforts by managers and organizations to motivate their employees through incentive and reward systems.

The fundamental cultural drivers are:

- Our concept of who we are.

- How we live in our surrounding environment.

- How we approach work.

Culture provides the stage upon which life events transpire, and people enter the workplace already imbued with a set of culturally derived work norms and values about what constitutes acceptable or fair working conditions, what they wish to gain in exchange for their labor, how hard they intend to work, and how they view their career.

3. Job attitudes

In a major study of job attitudes and management practices involving more than 8,000 workers in 106 factories in Japan and the United States, Lincoln and Kalleberg concluded that Japanese workers were less satisfied but more committed than their American counterparts. The researchers explained this difference through an in-depth examination of both Japanese societal culture and corporate culture.

For example, the age and seniority-grading system (nenko) prevalent in Japanese firms reinforces a family-like relationship between workers and companies. This, in turn, is reciprocated by workers in the form of stronger commitment to the organization.

By contrast, in the transitory culture that permeates many U.S. firms, less mutual concern exists between employers and employees. Employees frequently feel more like contract workers and have lower commitment levels.

The prevalence of after-work socializing among Japanese workers (tsukiai) was also cited as another way for workers to reinforce their friendship ties and trust levels.

Again, this contrasts sharply with the typical American practice of running for the parking lot or subway at the end of the workday.

Such differing work attitudes stem from specific cultural factors that, as we have seen, influence personal values and work motivation.

An attitude can be defined as a predisposition to respond in a favorable or unfavorable way to objects or the people in one’s environment. Attitudes have three interrelated components:

- Cognitive, focusing on a person’s beliefs and thoughts.

- Affective, focusing on a person’s feelings.

- Intentional, focusing on a person’s behavioral intentions.

Studies focusing on job attitudes tend to evaluate job satisfaction, job involvement and organizational commitment.

Although cross-cultural research on job attitudes is scarce, some evidence suggests that “country of origin” is a better predictor of job performance than any of the facets of satisfaction; that the relationship between locus of control and job involvement was culture-bound; and that aggregate work attitudes can change significantly over time as the result of structural changes in the political or economic environment.

Perhaps the most significant research suggests that the most satisfied employees are not necessarily found in richer countries or the countries of a particular continent. They are not found in countries that claim certain religious affiliations. Nor are they found exclusively in either large or small countries.

Instead, the most satisfied employees tend to be found in those countries where the prevailing management systems and motivational programs are compatible with and supportive of local cultures.

These findings caution against an unquestioning adoption of the “best practices” approach to management and motivation across diverse cultures.

In summary, cultural differences appear to have a significant influence on attitude formation, as well as on the consequences of attitudes once formed. Attitudes and accompanying trust levels influence the manner in which employees perceive and respond to reward systems. This, in turn, influences subsequent work motivation and performance.

Thus, as suggested many years ago by Porter and Lawler, ignoring the consequences of job-related attitudes on employee behavior and performance is done only at a manager’s or organization’s peril.

Lessons for motivating employees in different cultures

What lessons can be drawn concerning how to motivate employees in different cultures?

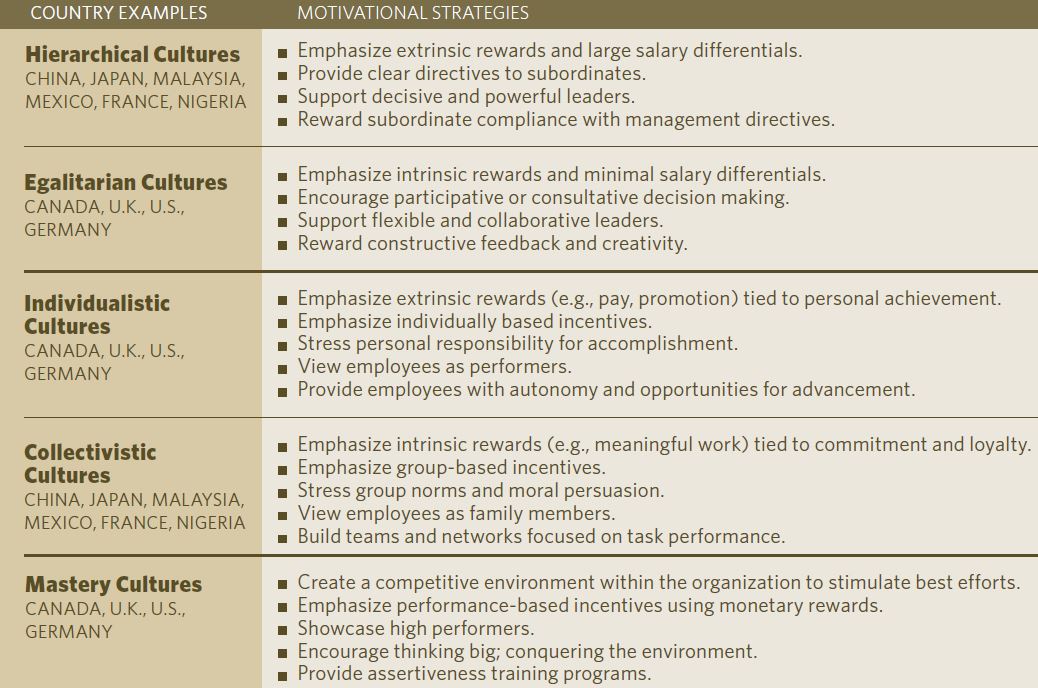

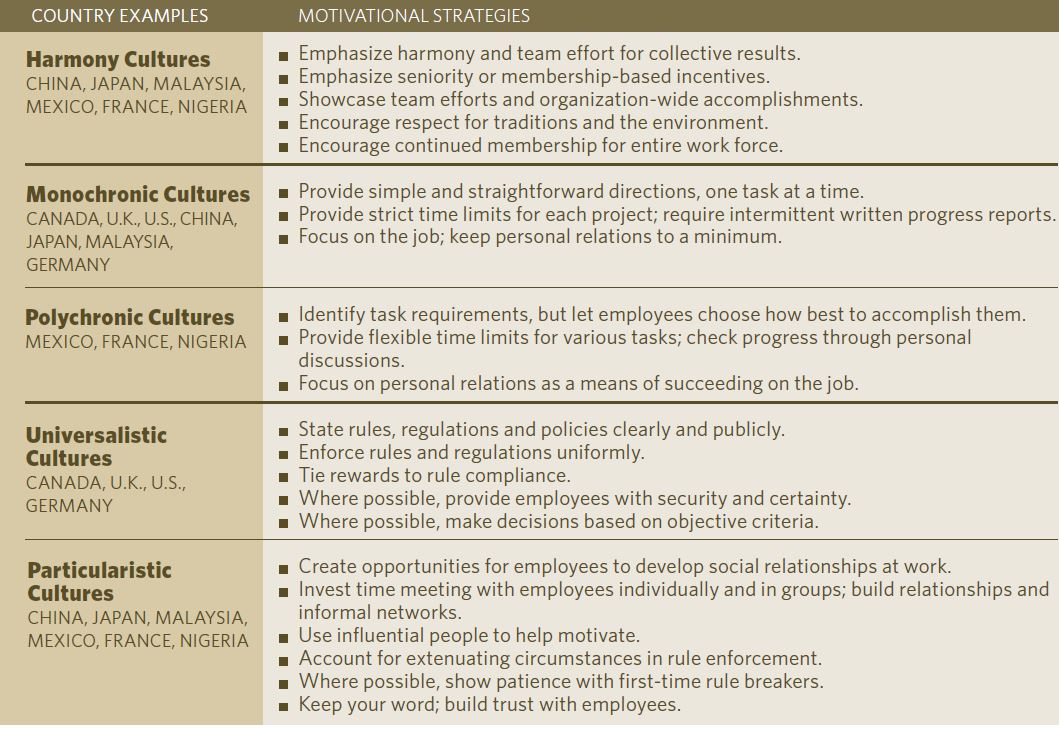

To answer this question, we can combine the research on employee motivation with models of national culture. We use five dimensions of culture:

- The extent to which power and authority in a society are distributed hierarchically or in a more egalitarian and participative fashion, measured on a continuum from hierarchical to egalitarian.

- The extent to which social relationships emphasize individual rights and responsibilities or group goals and collective action, measured on a continuum from individualistic to collectivistic.

- The extent to which people seek to change and control or live in harmony with their natural and social surroundings, measured on a continuum from mastery to harmony.

- The extent to which people organize their time based on sequential attention to single tasks or simultaneous attention to multiple tasks, measured on a continuum from monochronic to polychronic.

- The extent to which rules, laws and formal procedures are uniformly applied across societal members or tempered by personal relationships, in-group values or unique circumstances, measured on a continuum from universalism to particularism.

Finding the most appropriate motivational strategies and techniques depends largely on what culture managers are working in. The differences across these motivational techniques can often be substantial.

Consider just two examples:

- First, successful incentive programs in individualistic cultures would likely emphasize individual performance and emphasize financial rewards for outstanding performance, while such incentives in more collectivistic cultures would likely rely more heavily on group-based incentives and seniority-based rewards.

- Second, successful supervision in more hierarchical cultures would tend to be more directive, while supervision in more egalitarian cultures would tend to be more consultative.

In both examples, it can be seen that the successful motivational strategy will likely vary based on prevailing cultural characteristics.

The key lesson is this: Getting the most out of employees — and, ultimately, bolstering organizational success and the bottom line — requires assessing, integrating and adapting to various culture-specific factors that influence how workers feel, think and behave. Closer study of cultural nuances will benefit any manager seeking to excel in a global environment.

This article is published in IESE Insight Issue 5 (Q2 2010).

This content is exclusively for personal use. If you wish to use any of this material for academic or teaching purposes, please go to IESE Publishing where you can purchase a special PDF version of “Discovering what makes your employees tick” (ART-1786-E) as well as the full magazine in which it appears, in English or in Spanish.