IESE Insight

From stress to success: a diagnostic for navigating identity and change at work

Here’s what every company can do to check in with employees during times of change, managing transitions in ways that lower threat levels while boosting wellbeing.

Anna is a 39-year-old professor who had been working in her university for eight years when COVID-19 hit. The pandemic shut everything down and classes moved online overnight. She felt like one of the lucky ones, though, as some of her colleagues were let go. Later, as the lockdowns eased, it became apparent things weren’t going back to normal. The online teaching experiment had made the university rethink its entire educational offer and it decided that Anna’s classes should continue to be delivered online for the foreseeable future.

Anna felt panicked. It was one thing to teach online temporarily, quite another to make that the permanent solution going forward. Pre-COVID, the university had looked down on online-only courses, regarding them as inferior to the in-person, high-touch campus experience. Now it seemed that no longer mattered. Anna herself preferred interacting with students on campus and the camaraderie with staff. Facing a future isolated from all that, Anna no longer knew what it meant to be a teacher. A former colleague who had left during COVID told her about a job opening in his university, where the teaching was in-person as before. Anna was seriously considering quitting.

Anna is fictional but the situation is real. Anna is facing an identity threat — an experience when a person’s perception of who they are, the group they belong to, the relationships they have and their role in society is suddenly called into question, undermining what they thought they knew before.

When this happens, the person, like Anna, may get stressed, feeling like they’re not up to the new task required of them. This can lead to drops in performance, burnout and higher turnover intentions as, to escape the threat, the person may be tempted to quit their job or exit their profession entirely.

Teachers are one of the groups I studied as part of research with Karoline Strauss (ESSEC), Julija N. Mell (Erasmus University Rotterdam) and Heather C. Vough (George Mason University). Besides wanting to figure out what triggers identity threats, we wanted to come up with a way for researchers and managers to gauge what employees might be feeling, especially if there is a change as big as what Anna was anticipating. With that understanding, we suggest some actions managers can take to lower threat levels, helping people move from stress to success.

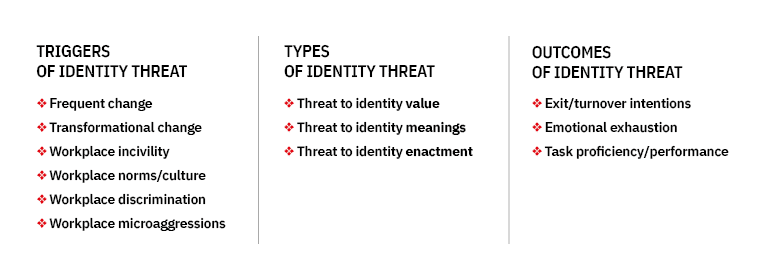

Triggers of identity threats

Teachers grappling with the prospect of online teaching were the first of three samples we studied. We chose teachers because their work-related identity threat will be familiar to many people similarly facing technological disruption to their current profession. Transformational and frequent change that challenges people’s values and ways of working is a common trigger today.

Another common trigger is workplace incivility, linked to workplace norms and the culture in which such norms are formed and allowed to flourish.

Consider Fiona, a 32-year-old who works in finance, with 10 direct reports, all men. Her team is highly competitive, as a significant portion of their compensation is performance-related. They work long hours and never switch off, not at night, not on weekends and never during vacation — if they even ever take a vacation. As a young-and-hungry executive, Fiona was a rising star in the firm where she had been working for the last five years after being recruited straight off her MBA. Then, she got pregnant.

At 22 weeks, she could no longer hide the fact from her team. She felt their eyes on her in meetings. When someone mentioned they foresaw an imminent “bump” in business, she heard the sniggers. When the usual call went out for ordering lunch, colleagues eye-rolled about not ordering sushi for her sake. They stopped inviting her for beers after work. Worse, they openly jockeyed to replace her once she went on maternity leave.

One day she found one of her team in her office with his feet on her desk: “Just practicing,” he joked. “Let’s face it, once the baby comes, you’ll probably want to stay home and not come back. That’s what happened to my wife. It’s natural.” When she got angry, the other men on the team muttered, “Hormones.”

For this sample, we adapted our measures slightly to account for the unique threats faced by pregnant leaders. We also measured incivility and masculine contest culture (like the one described in Fiona’s firm) through statements such as, “Since being pregnant, my supervisors, colleagues or reports have displayed incivility like putting me down or being condescending to me” and “In my work environment, admitting you don’t know the answer looks weak.” We then assessed whether pregnant leaders were thinking about quitting, through statements like, “I frequently think about abandoning my leadership role.”

Although the subjects we surveyed were pregnant leaders, we can think of this trigger in broader terms of life-changing events. So, a person who sustains a physical injury that changes their ability to enact their previous identity (as other studies have explored, involving professional musicians who can no longer play their instrument after an accident, for example) would also fall into this category of triggering event.

The final set of triggers relates to workplace discrimination and microaggressions arising from nonwork identities — in other words, identities related to personal characteristics that are core to the person, such as their race, ethnicity, age, parental role, gender, religion or sexual orientation.

For this sample, we added statements like, “I don’t get paid as much because of my identity” and “I have had my behavior mimicked in a joking way due to my identity.” We also included, “I often think about leaving my current employer,” given that turnover intentions generally rise for this identity threat.

The subjective nature of identity threats

There is no shortage of identity-threat triggers. There could be others, like a corporate scandal or a merger and acquisition.

For our research, we sorted through myriad scholarship on the subject to develop a standardized grouping to measure this ubiquitous experience. By testing it with our three samples, we were able to ascertain that certain difficult workplace experiences are associated with certain outcomes.

But the fact that workplace discrimination might provoke stress or turnover is no surprise; what’s interesting is understanding how the person’s processing of that trigger plays a role in the eventual outcome.

With that insight, organizations are in a better position to manage such changes and workplace experiences according to how people perceive them, and take remedial action.

We validated three ways that a person perceives a difficult workplace experience:

- as a threat to identity value: the person feels their given identity is being devalued.

- as a threat to identity meanings: the person’s current understanding of their given identity is no longer sustainable.

- as a threat to identity enactment: the person feels the new experience is going to limit or prevent them from expressing their identity as fully as they did before.

The subjective nature of the threat is important to consider here. That’s because not everyone will perceive or react to the same workplace experience in the same way.

For example, the introduction of new technology may leave one person feeling threatened while another might not.

Additionally, a given experience, such as the introduction of new technology, need not generate all three types of identity threat: Employees might find the meaning of their work changing yet at the same time feel no less valued and still be able to engage in activities and interactions that let them express their identity.

Moreover, it’s not inevitable that when identity is threatened, people will automatically quit or exit. They could still reframe the threat as an opportunity — a chance to learn and grow — and subsequently reappraise their identity, deriving positive new meanings, value and expressions.

For organizations wanting to help their people through change, this is the goal.

Take the pulse of your employees

To help ensure your own organizational triggers don’t provoke negative or undesired outcomes, it’s vital to take the pulse of your employees. I recommend managers go through a similar exercise as we did in our study.

Maybe you’re thinking of implementing a change like switching from in-person to online working or, as is increasingly the case today, mandating remote workers come back into the office full-time. Or maybe you’re rolling out AI software, which is radically restructuring people’s work.

It doesn’t have to be anything radical, either: you may simply want to check in with people going through personal, life-event transitions; or maybe something is happening in the wider social and political environment that is affecting the way people perceive themselves and their identities.

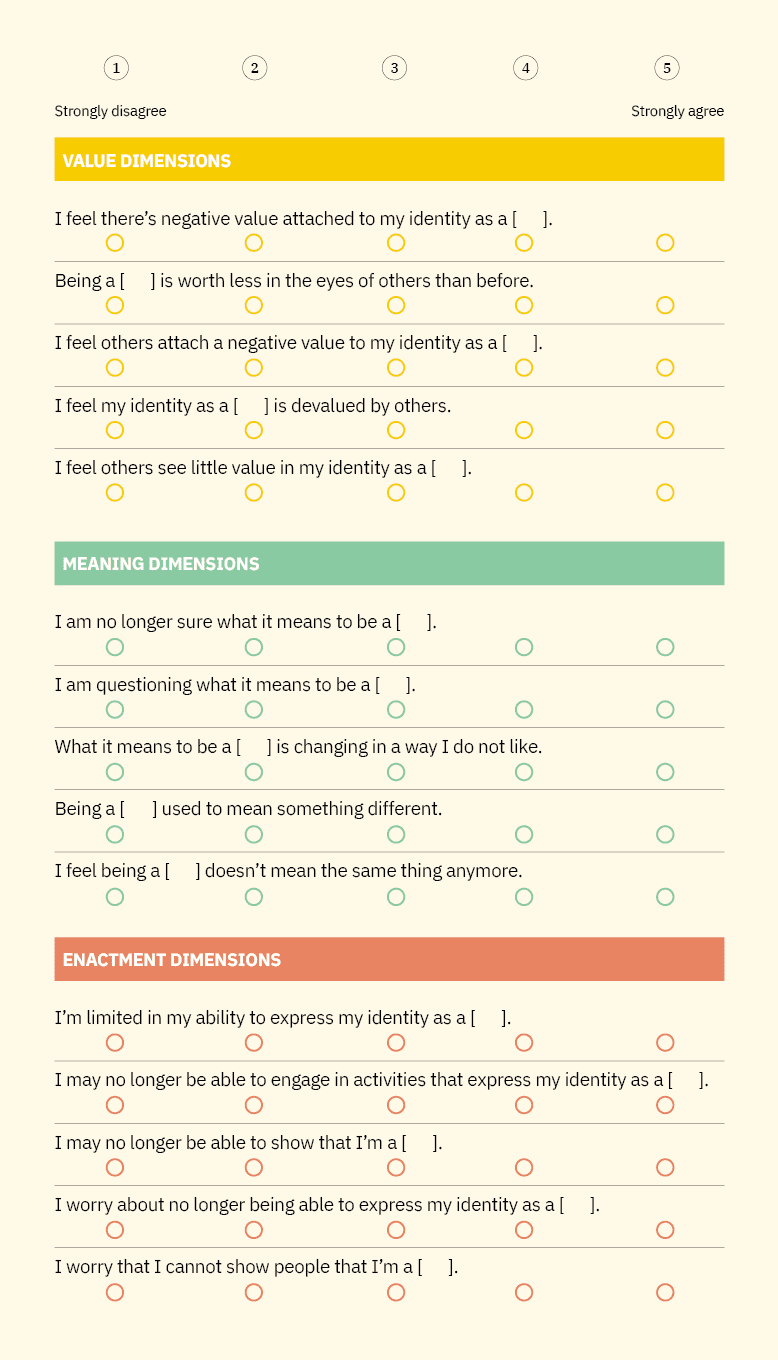

Use our sample survey as a diagnostic tool

Ideally, our survey would be done before any changes are announced to measure the pre-state of affairs. This gives managers a frame of reference to go back to when repeating the survey after the transition. This is helpful to understand how people’s perceptions may have shifted and whether threat levels have gone up, down or remained the same.

These surveys are best done anonymously so employees feel able to express themselves truthfully. They could be done at the level of a team, a department, a business unit or be company-wide, administered by a manager or by HR, depending on the situation.

The aim is to tease out which identities are under threat: are they related to value, meanings, enactment or a mix?

The following statements should be presented in randomized order, so participants do not see the items grouped. Approaching the same dimension from different angles lets you scale the answers, so you can tease out more accurate results. Statements can be adapted, like we did in our study, according to the nature of the change or threat.

Instruction: Please take a moment to think about the change in question. The following statements are concerned with how your identity as a [specify the identity] is affected by this experience. Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with each statement on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Drilling down into your employees’ identity threats is indispensable for revealing pain points in the change management process.

Depending on the nature of the identity threat, managers can then design and implement precise interventions — from helping employees regulate their emotions, to providing additional training or reskilling, to tackling any toxic behaviors, to improving workplace dynamics that boost everyone’s wellbeing and performance.

Going back to our survey of teachers, knowing that online teaching threatened some in their enactment — their ability to engage in activities and interactions that let them express their teacher identity — the school could make some accommodations. Perhaps they could establish a space on campus where faculty could still go to interact with their students. Or maybe they could build a face-to-face component into the curriculum to serve the need for offline contact.

There are various ways that organizations can allow people to continue with those behaviors that they cherish as part of their work identity — if they ask.

It also requires probing their answers to get at the underlying value under threat. Is it because they associate the change with a loss of freedom or autonomy? Is it because they can’t do parenting the way they really want to? It may not have anything to do with the actual change being proposed. Understanding all of these different facets helps in being able to provide appropriate solutions.

What makes you feel threatened?

Finally, to maximize the effectiveness of the assessment, managers themselves need to be open to genuinely listening and sincerely dedicated to addressing employee concerns. For that reason, I recommend using our survey as a self-diagnosis tool.

What makes you feel threatened?

Reflect on whether it threatens you because of feeling undervalued, because of a fundamental disagreement on the meanings you ascribe to your identity, because your ability to enact your identity — to be your authentic self at work — is affected, or because of a mix of factors.

It can be beneficial to do this self-check under the guidance of a professional mentor or coach. The better you know your own triggers and identity threats, the more sensitive and aware you will be in helping others through the same process.

MORE INFO: “When ‘who I am’ is under threat: measures of threat to identity value, meanings and enactment” by M. George, K. Strauss, J. Mell and H. Vough is published in the Journal of Applied Psychology (2023).

Another version of this article was also published in Forbes. Read more insights from IESE Business School’s global experts at Forbes.

This article is included in IESE Business School Insight online magazine No. 170 (Sept.-Dec. 2025).

SEE ALSO: “Plug in, ponder or pause? How global professionals’ prior identity tensions affected their responses to pandemic-induced disruptions” by B. Sebastian Reiche and Mailys M. George, published in Academy of Management Discoveries (2024).