IESE Insight

Why immigrants earn 18% less than natives and how to narrow that pay gap

Limited access to high-paying jobs explains 75% of the immigrant pay gap, according to a study of European and North American countries.

With immigration at the center of global policy debate, a new study shows that immigrants to Europe and North America earn nearly 18% less than natives, as they struggle to gain access to jobs in higher-paying industries, occupations and companies.

The research, published in Nature, analyzes employer-employee data on 13.5 million people from nine immigrant-receiving countries in Europe and North America: Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden and the United States. It was conducted by researchers from more than a dozen universities around the world, including IESE’s Marta Elvira and Halil Sabanci of the Frankfurt School of Finance and Management and an IESE PhD.

The study quantifies the pay gap between immigrants and natives in the nine countries and identifies the source of salary disparities: whether immigrants earn less because they’re shut out of higher-paying companies and jobs; or whether they’re paid less than non-immigrants for doing the same job in the same company.

The immigrant-native pay gap

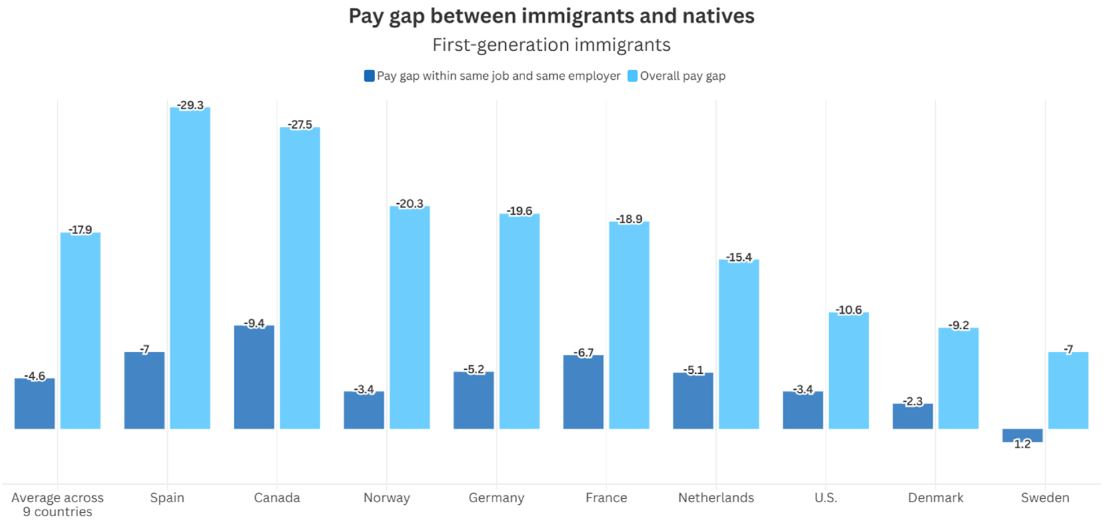

The immigrant-native pay gap, which stood at 17.9% overall, is primarily driven by immigrants’ limited access to higher-paying industries, occupations and companies (known as sorting), rather than by unequal pay for equal work, the research finds. More precisely, three-quarters of the gap was due to sorting into lower-paying employment and the remaining quarter was due to differences in pay for the same job and company (known as within-job inequality).

is the average wage gap between immigrants and natives.

That means policymakers should focus on improving access for immigrants, through measures such as language training, skill development, job search assistance, domestic education opportunities, foreign credential recognition and enhanced access to job-relevant information and networks. Policies targeting employer bias in hiring and promotion decisions may also be effective.

“Prioritize initiatives to improve immigrants’ job access,” the authors wrote in a policy brief accompanying the Nature article. “Equal-pay policies are important but closing the immigrant pay gap requires improved access to better-paying jobs.”

Immigrant pay gap narrows over time

In countries where data was available (Canada, Denmark, Germany, Netherlands, Norway and Sweden), the researchers also looked at the native-born children of immigrants to discover whether the same earnings patterns continued across generations.

For the second generation, the overall gap had narrowed to 5.7% but still persisted, especially for children of immigrants from Africa and the Middle East. The within-job difference in pay was, on average, 1.1%.

Some additional findings:

- The pay gap varied widely among countries for first-generation immigrants. Spain (29.3%) and Canada (27.5%) had the largest overall gaps. Norway (20.3%), Germany (19.6%), France (18.9%) and Netherlands (15.4%) saw mid-level differences. The smallest differences relative to natives were found in the U.S. (10.6%), Denmark (9.2%) and Sweden (7.0%).

- For the second generation, the pay gap had narrowed to an average 5.7%. By country, the differences were: Norway (8.7%), Germany (7.7%), Netherlands (5.5%), Sweden (5.3%), Denmark (5.2%) and Canada (1.9%). About 80% of the difference was due to sorting. The within-job pay gap was 1.1%.

- By region of immigrant origin, the average overall pay gaps were: sub-Saharan Africa (26.1%), Middle East and North Africa (23.7%), Asia (20.1%), Latin America (18.5%) and Europe, North America and other Western countries (9.0%).

Immigrant pay gap largest in Spain

Spain stands out for its particularly high pay gap, despite the fact that economic growth in recent years has been fueled, in part, by immigration.

Spain became an immigrant-intensive country later than other countries in the study, and may need to refine processes for fully integrating people of different backgrounds into the workforce. Immigration to Spain took off in the early 2000s, leveled off in the decade after the 2008 financial crisis, and has surged since 2018. People born outside of Spain now account for 18% of the population, a figure that is expected to more than double in the next 50 years, according to official estimates.

Immigrants in Spain also overwhelmingly work in areas such as tourism, caregiving, agriculture and construction, fast-growing but low-paid sectors, and in small to medium-sized companies. Contracts are often temporary or part-time, which undermines pay. Immigrants have limited access to public-sector employment, which in Spain tends to be stable and well-remunerated.

In addition, there is a relatively smaller number of more affluent immigrants from the rest of Europe and North America; the vast majority are from northern Africa and Latin America.

Policy recommendations for closing the gap

Given that the root of the salary inequality is access, governments should:

Training

Invest in language training, education and vocational skills for immigrants.

Access

Ensure immigrants have early access to employment information, networks, job-search assistance and employer referrals.

Acknowledgment

Implement standardized and transparent recognition of foreign degrees and credentials, helping immigrants to access jobs matching their skills and training.

Transparency

Root out employer bias in hiring and promotion practices through greater organizational transparency and managerial accountability.