IESE Insight

A framework for dealing with corporate legacies of irresponsibility

A constructive approach for organizations to right past wrongs and foster justice through retribution, reparation, reintegration and reform.

By Jordi Vives-Gabriel

Saying sorry, taking responsibility for past wrongdoings and trying to make amends for the hurt caused: these seem uncontroversial practices. They’re core tenets of ethics, moral psychology and Christian teaching.

Yet in 2025, “sorry” seems to be the hardest word to say. This is especially the case for organizational wrongdoings committed in a distant past, and even more so in a world marked by a pendulum swing away from any activities deemed “woke.”

Corporate diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) programs are being axed, and public support for reparations, which reached historically high levels during 2020’s racial justice protests, appears to be waning. This, even as the African Union has designated 2025 as the Year of Reparations, urging Western powers to right the past wrongs of slavery, colonialism and apartheid.

What does this mean for organizations today? We’ve seen many organizations genuinely trying to address their “legacies of irresponsibility,” from historical ties to the slave trade to complicity in environmental disasters. Yet does it make sense for an organization to wrestle with what its predecessors did decades or even centuries ago? What can realistically be done about it now?

This is what I explored in the paper, “Dealing with organizational legacies of irresponsibility,” coauthored with Judith Schrempf-Stirling (University of Geneva) and Diego M. Coraiola (University of Victoria). We argue that modern organizations do, in fact, have moral obligations toward their past. These responsibilities extend beyond legal liabilities or corporate image concerns. We developed a practical framework for organizations to reckon with legacies of irresponsibility.

Why should I care about things that happened in the past?

Today’s leaders might reasonably ask: Why should I be held responsible for the misdeeds of my predecessors?

This is a fair question that has long preoccupied moral philosophers. Here’s how they answer: Success today is often built on foundations laid the past. We are “standing on the shoulders of giants,” as the saying goes. And just as we have inherited profits from the past, so, too, did we inherit the responsibilities that come with them.

Organizations are essentially communities that hold the collective memories, values and benefits from earlier times. Indeed, many organizations — not just companies but churches and football clubs — carry this deep sense of intergenerational endowment. Their very existence is owed to previous generations, and the work they do today is designed not only to honor that past but to outlive the present, and serve future generations as part of an ongoing social contract.

Guilty as charged: What can I do about it now?

If we accept those arguments and belong to an organization with such legacy concerns, then the next question becomes: What can I do about it?

When “reparations” are talked about in the media, it’s usually about offering monetary compensation — that’s what grabs headlines. It’s also what makes organizations reluctant to engage with the topic, because the cost of paying compensation to victims and their families can tally into the billions, and who has that kind of money to play with today?

Yet, as our research shows, even if organizations choose to ignore their past, their stakeholders rarely do. Corporate silence also comes with a cost. Public memory can be remarkably persistent, and an organization that appears evasive or complicit in shirking or perpetuating the harms of its past can be extremely damaging to its brand reputation and ultimately impact the bottom line and the sustainability of the business.

Besides, money isn’t the only form of reparation. For example, when the British newspaper The Guardian decided to take the topic seriously in 2020, its owners, the Scott Trust, set up an independent commission to do academic research on the historical links between the paper’s founders and the transatlantic slave trade. The findings were published in 2023, detailing those links. And though the Scott Trust did set up a monetary fund to invest in descendent communities linked to the founders, it went further: It issued a public apology and set out a 10-year plan of restorative justice, including an ongoing series called Cotton Capital, directing its journalism to tell the stories of how slavery and its legacies shaped Manchester, Britain, Jamaica and the rest of the world. As one article from the series pointed out: “It’s not just about payment. It is about engaging in good faith with the descendants of enslaved people and addressing inequalities — to make a better future possible.”

In a similar spirit, we propose a framework to help organizations with troubled histories face up to and respond to them in meaningful ways.

A 4-sided approach to justice to redress organizational legacies of irresponsibility

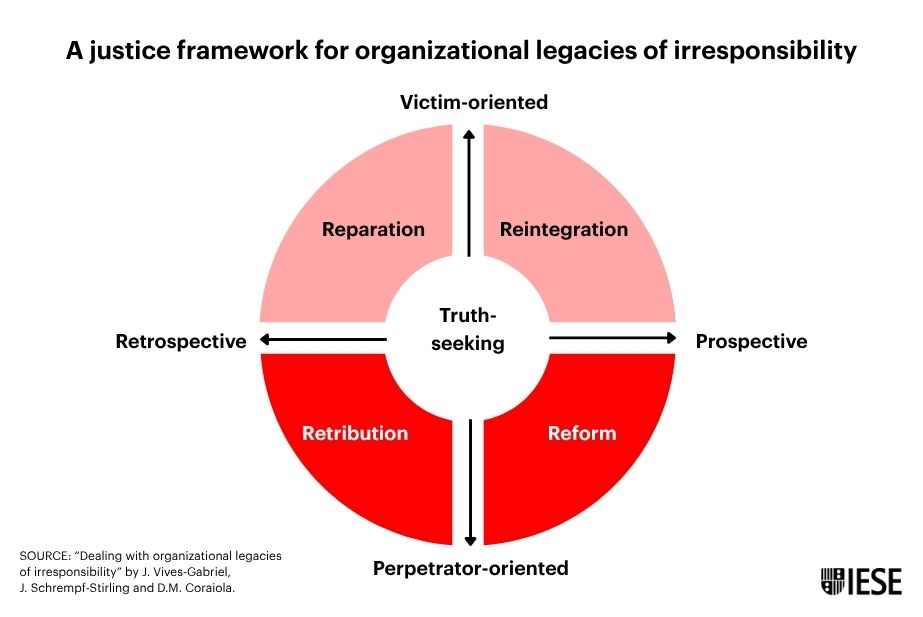

Our framework for addressing legacies of irresponsibility is built around four interconnected components: retribution, reparation, reintegration and reform. The basic idea is that, before offering any kind of amends for past wrongs, you must first confront the facts of what happened, who was impacted, and how your organization was involved. It is not about you controlling the narrative. It is about hearing the different truths held by the affected communities and honoring them.

1. Acknowledge through retribution

In some cases, taking responsibility means a company must face the consequences — not necessarily through the courts, but by choosing to give something up, such as profits or certain business deals.

For example, German chemical company Degussa faced a backlash when it won a contract to provide materials for a Holocaust memorial, despite the company having profited long ago from supplying poison gas to Nazi death camps.

Some suggested Degussa could have avoided criticism by stepping back from the contract. Another option would have been to contribute the materials at no cost and without seeking public recognition.

When a company makes such choices voluntarily — as a form of self-imposed retribution — it can send a powerful signal of sincerity and humility.

2. Engage in meaningful reparation

Reparation means trying to make up for past harm. This can include money, as previously mentioned. But reparation can also take other forms of support for affected groups, including symbolic acts like making a public apology, changing the names of buildings or installing memorials. These can carry moral weight.

In addition to The Guardian’s reparation action in 2020, the British insurer Lloyd’s apologized for its role in insuring voyages transporting millions of enslaved people. It also pledged to invest in new initiatives to attract, support and advance Black and minority ethnic professionals.

Even for organizations that opt for monetary reparations, there are ways of structuring them that don’t bankrupt you. Georgetown University, for example, reckoned with its past selling of 272 slaves in 1838 to keep the institution afloat by pledging to deposit $400,000 annually in a reconciliation fund to help those slave descendants. This fund is raised from levying an extra $27.20 per student per semester, which was voted on and agreed via a student referendum. As the American Civil Liberties Union notes, this demonstrates how reparations can be made that serve the cause of justice without leaving the institution in debt.

The important thing is to avoid cheap talk. Apologies, while necessary, are not sufficient on their own. Stakeholders will look for action, which is why symbolic and material repair are most powerful when combined.

3. Support reintegration to build a better future

As well as looking back (the retrospective side of the framework), companies need to look forward (the prospective side). This is where reintegration comes into play, which means focusing on how to create a fairer future for those harmed by dark corporate legacies.

As before, reintegration can take the form of financial support for descendants of groups who were harmed. Scholarship programs and special internships aimed at rectifying entrenched inequality or the exclusion of certain groups are common tools that organizations can adopt, recognizing that the impact of past harm is not left to history but continues across generations to this day.

However, as Bloomberg reported, groups that had been working to recruit underrepresented students to higher education programs — including the Consortium for Graduate Study in Management, Prospanica, Management Leadership for Tomorrow and the Forté Foundation — have recently noted a sudden withdrawal of participating institutions, allegedly in reaction to a U.S. Department of Education letter warning any educational institution that receives government funding to back off efforts to redress past inequities. With the reintegration part of addressing legacies of irresponsibility having become so politicized, organizations will have to tread carefully in how they walk this path in the current climate.

4. Commit to institutional reform

The final action of the framework — reform — is aimed at ensuring past harmful acts are never repeated. Often, organizations will need to reform their internal policies, structures and cultures to prevent future wrongdoing.

For instance, Volkswagen implemented a youth exchange program, connecting younger generations from Germany and Eastern Europe, where former forced laborers of Volkswagen came from. The program educated participants about German history and its consequences, holding awareness-raising, knowledge-sharing seminars at the former concentration camp of Auschwitz.

These kinds of reforms signal a clear break from past practices and reflect a commitment to longer-lasting change.

A living process, not a one-and-done

All this said, there is no silver bullet for addressing legacies of irresponsibility. Different legacies require different responses. Some victims want recognition; others seek compensation or structural change.

What matters is that organizations enter into the process openly, with sincerity and transparency.

Reconciliation, ultimately, is not declared by the company. It is granted — if at all — by the communities who were harmed. And it often requires long-term engagement, not a press release or a one-off story in the annual report.

In this highly polarized and politicized environment, it may seem a risky time to embark on a soul-searching process of addressing legacies of irresponsibility. Yet doing so may, in fact, be the first important step toward remedying the underlying causes of our current condition. To paraphrase a well-known adage: Those who don’t deal with the past are condemned to repeat it.

MORE INFO: “Dealing with organizational legacies of irresponsibility” by Jordi Vives-Gabriel, Judith Schrempf-Stirling and Diego M. Coraiola. Academy of Management Perspectives (2024). This paper was recognized with a 2025 Best Article Award and was featured as “How organizations can right past wrongdoings” in Academy of Management Insights.

“Moral repair: toward a two-level conceptualization” by Jordi Vives-Gabriel, Wim Van Lent and Florian Wettstein. Business Ethics Quarterly (2022).

ALSO OF INTEREST:

Business & Inequality: Purpose-driven strategies to create a more equitable world

Reflection points:

- How do you feel about legacies of irresponsibility?

- Which activities of the framework presented resonate with you or would your organization find most challenging to implement?

- If any issues raised in this article apply to your organization, what steps can you take to begin to address them?