IESE Insight

Why your biggest cybersecurity risk isn’t technology — it’s your people

Use this framework to build a strong privacy culture, adding zero-trust behavioral safeguards to your technical defenses.

In 2024, an employee in the Hong Kong office of the U.K.-based multinational firm Arup dutifully transferred £20 million to various accounts after being apparently asked to do so by the company CFO. Initially, when the employee received an email supposedly from the London office asking for the secret transactions to be made, he was rightfully suspicious. But then he held a videocall with the CFO and other staff he recognized, so he obliged. Only later it turned out the videocall was a deepfake using AI-generated voices and images, and the entire request was an elaborate scam. “Like many other businesses around the globe, our operations are subject to regular attacks, including invoice fraud and phishing scams,” a company spokesman said. “But the number and sophistication of these attacks has been rising.”

This story illustrates an important truth about cybersecurity, encapsulated in this testimony by convicted hacker Kevin Mitnick: “The human side of computer security is easily exploited and constantly overlooked. Companies spend millions of dollars on firewalls, encryption and secure access devices, and it is money wasted because none of these measures addresses the weakest link in the security chain — the people who use, administer, operate and account for computer systems that contain protected information.”

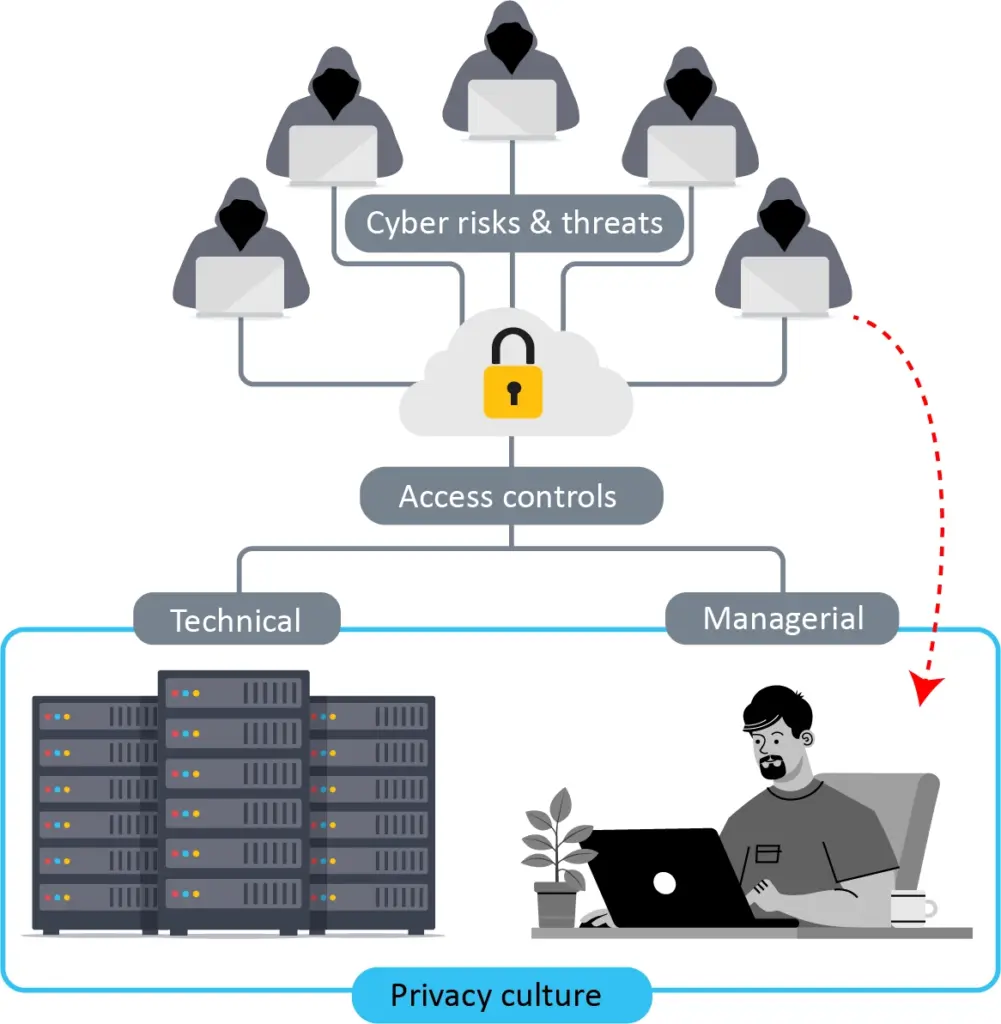

Consider this graphic:

There are ever-present cyber risks and threats, and companies try to mitigate their impact or avoid them altogether by applying access controls — literally controlling the access into the system. They do this by introducing a multitude of information technology (IT) and operational technology (OT) protections like encryption, firewalls, security protocols, two-factor authentication, backups, patches and so on. And while these layers upon layers of technical protection are absolutely essential, they are not enough because they do not address the human factor, which exists as its own layer.

This is why technical protections need to go hand-in-hand with managerial controls, which is the focus of this article. By managerial controls, we’re talking about more than providing employees with Security Education, Training & Awareness (SETA). Such programs teach employees the basics — don’t share passwords, update your software, don’t click on suspicious links — but they fail to address the potentially more serious errors that humans make in their everyday privacy decisions. No matter how rigorously you design the left side of the graphic to keep hackers out, all is for naught if you neglect the right side, and a gullible employee unwittingly invites hackers in through the back door. After all, it is easier to “log in” than “hack in.” So, where is your company focusing its effort?

In a recent IESE webinar on cybersecurity, I asked the audience: How often do you click “accept all” cookies when visiting websites? The majority said most of the time or sometimes, with less than a third saying they always rejected cookies. Although that rejection rate was higher than it used to be, it’s not as much as I think it should be, especially when you consider the other question I asked: Have you ever experienced or been affected by a cyberattack, personally or at work? The overwhelming answer was yes, and for the small minority who said no, it’s likely they had been breached but just weren’t aware of it yet. And as the Arup case shows, cyberattacks are growing ever more sophisticated, so no one can afford to let down one’s guard.

The vital importance of a privacy culture

What’s needed as much as SETA is PETA — Privacy Education, Training and Awareness. If, as studies estimate, 80% to 90% of breaches come down to human error, then companies need to pay as much attention to their human privacy culture as they do to their IT/OT systems.

A company’s privacy culture refers to the collective values, beliefs and practices that are deeply embedded in its operations and which guide how data management and the protection of personal information are approached and prioritized. It encompasses the attitudes and behaviors of employees at all levels of the company, emphasizing the importance of safeguarding privacy and personal data. It requires being proactive about upholding privacy standards, with company-wide training and a shared commitment to ensuring that data protection principles are integrated into all operations, decision-making processes and strategic objectives. That is why, in the graphic, privacy culture covers both the technical and managerial sides of a company’s security controls.

In research with colleagues in Brazil, Saudi Arabia, the United Kingdom and the United States, we developed a framework to support the development of a corporate privacy culture.

To establish a baseline understanding of privacy, we began by surveying over 1,000 employees across multiple departments (including sales, procurement, marketing, strategy and governance) and across various sectors (including manufacturing, technology, health, retail, e-commerce and sports clubs). We asked them a series of questions, first about their privacy expectations and then their perceptions of their company’s current practices. We also gauged their general behaviors (through statements such as “I know what to do if I notice or experience a security incident or data breach”) and assessed their responses to specific situations (through a series of “what would you do if…” types of questions). We also referenced existing legislation, such as the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). This yielded a composite index of 10 privacy culture pillars, summarized below.

10 pillars of privacy culture

1. Information security

Appropriate measures (policies, procedures and systems) are in place, followed and monitored by collaborators to protect the personal data of data subjects.

2. Risk management

The organization has defined risk levels and up-to-date documentation for privacy and data protection risk management, including assessing, monitoring and reporting risks to the parties involved.

3. Transparency

Privacy policies and personal data access controls are reviewed regularly and are made available for easy access. Relevant changes related to data use are proactively communicated to those affected.

4. Organizational governance

A well-defined organizational structure is implemented with clear and communicated roles and responsibilities, supported by the board and executives, and appointed “privacy champion” collaborators.

5. Processing purposes

People in the organization know why they are handling personal data and what the legal basis of handling is for each activity.

6. Data sharing

There are signed and up-to-date contracts and/or agreements for the processing of personal data with all third parties with whom personal data is shared.

7. Data subject rights

Customers, users and employees receive instructions on how to exercise their privacy and data protection rights, and the organization has a clear structure and procedure to serve them.

8. Incident management

There are clear processes for identifying data security incidents and leaks, including assessment and communication of such incidents to affected parties and authorities.

9. Training

The organization has policies, training and support available, which are easily accessible to its employees, and participation in training is monitored by the company’s managers on a regular basis.

10. Processing principles

The organization has operations and procedures in place to ensure that the processing of personal data is limited to necessity, has a defined scope and the data is only kept for as long as needed.

Having established this baseline index, we repeated the survey a year later with a further group of over 1,400 employees from equally diverse departments and sectors. This benchmarking step allowed us to see whether and how privacy culture was evolving in companies, and to identify gaps between expectations and practices, between general behaviors and situational responses.

Comparing results from one year to the next, we observed small improvements across all 10 pillars, which is somewhat reassuring. However, gaps persisted, notably between employee expectations and current company practices.

Analyzing the data by roles, we also saw that company leaders scored lower than operational staff in both years. This is troubling, since the leaders are the ones responsible and who will be held accountable for ensuring data protection policies are in place and that the company complies with relevant laws and regulations.

Once such gaps are identified, companies are then better equipped to make targeted interventions. As one data privacy officer remarked, going through this exercise made the company aware of which areas to prioritize for improvement.

The index serves as a useful reference for companies to evaluate the state of their privacy culture and maturity levels, highlighting vulnerabilities to address with employees. (The exact questions we used can be found in the appendices of our paper, if people are interested in using our assessment tool as a reference and adapting it to their own context.)

We summarize the three steps of our framework as the 3B’s:

Baseline

Conduct a thorough internal privacy culture assessment to check your current state of play, establishing your own baseline index that identifies key areas to focus on within your company.

Benchmark

Compare the results of your privacy culture index with relevant industry standards and best practices. Also, as you repeat this exercise annually, you can chart how you are progressing on internal privacy culture year over year.

Bridge

Close gaps identified in the prior steps, both internally (discrepancies between company practices and aspirations) and externally (your company’s position relative to competitors and the market).

We believe this approach constructively shifts the focus from mere technical or compliance strategies to thinking about data privacy and security more holistically, aligning employee behaviors with leadership goals and organizational objectives. Crucially, it enlists employees in the process, since they are often the first line of defense against cyberattacks and data breaches.

Make employees aware of their own vulnerabilities

Why are employee-centric privacy training programs so important? Let me illustrate with an experiment I did involving two groups, testing their propensity to disclose private information. Everyone took part in a security awareness workshop teaching them about the risks of phishing emails and so forth. Everyone completed a survey immediately before the workshop, one immediately after and another two weeks later, asking questions like, “Do you use the same password for multiple websites? Do you include your birthday when creating a password? Do you share personal details on social media?” In the control group, people could answer yes/no or skip, while the treatment group could answer yes/no or choose “I prefer not to provide this information.” This “privacy nudge” essentially served to make people explicitly aware that they did not have to answer if they didn’t want to. And those who received that nudge ended up sharing less information than those who didn’t.

This suggests that one ingredient of a good privacy training program should be to make employees aware of the behavioral psychology at work behind their privacy decisions. Simply giving a person the chance to pause and reflect before making a privacy decision (as the nudge served to do) can help employees resist making an automatic, unthinking, potentially risky data giveaway.

Another experiment I’ve done showed that when people are in a happy, relaxed state, they’re also more likely to reveal personal information compared with those in a neutral state, despite having privacy concerns. Again, if human error is the biggest cause of security breaches, then training humans to resist privacy fatigue and making them aware of various psychological tricks at play will help prepare them for better privacy decision-making.

This video is a stark example of how scammers keep devising ever more devious ways of emotionally manipulating people and getting them to reveal sensitive private information. Educating your employees to know which human factors can be exploited is another privacy firewall for your company.

Privacy penetration testing and privacy champions

To reinforce a privacy-first mindset throughout the organization, I recommend reverse engineering — starting with the problem and then working backward to analyze exactly where the weak links in the chain of events that led to the problem occurred, so they can be tackled directly. Companies frequently do this in security penetration testing, enlisting ethical hackers to test their networks and systems to detect software and hardware vulnerabilities and flaws, and thereby strengthen their technical defenses. I argue for companies to be equally proactive in doing privacy penetration testing, though here what we are reverse engineering are not IT/OT systems but the human brain.

As with technical penetration testing, we start with information gathering — the surveys of my research. Bear in mind that this exercise can be provocative as it is exposing personal weaknesses. However, it’s important to remind participants that any vulnerability they may feel is a necessary part of the experiment, which is purposely done in a safe space or “sandbox” with the aim of preventing the true victimization they will undoubtedly feel if they are actually tricked like the hapless Hong Kong employee was.

It helps if there is a high level of trust in the organization; if not, you may need to spend time building it, as the learning experience will be greater if people feel safe to be transparent about their actual behaviors and genuinely share information without fear of reprisal. Once armed with meaningful information, managers are then in a position to take targeted action: establishing clear policies and guidelines, like our 10 pillars, with associated behavioral procedures for employees to follow.

Allied to this is appointing “privacy champions” across departments and integrating privacy considerations into governance structures to help ensure sustained engagement. You need people who are passionate about privacy and have a wealth of knowledge, particularly when it comes to psychology and behavioral economics. Hackers are experts in manipulation, so you need the equivalent of a “white hat” in your organization. Logically, this role would fall to the CTO or CIO, though these roles tend to focus on the technical side, not the human side. To deal with GDPR, many companies will have a Data Protection Officer (DPO) who, in theory, should help to drive this agenda, but they often get mired in legal compliance issues and paperwork rather than PETA. Ideally, though, the DPO would be the lead champion, working in close collaboration with HR. Indeed, PETA should form an integral part of any onboarding process, establishing the organizational baseline as you build your benchmarks. Companies should also prioritize privacy penetration testing for their customer service teams, given their more vulnerable position, making them your first line of defense (remember the video).

Ensuring a privacy culture takes root among frontline workers is perhaps the best immediate safeguard, because you are tackling day-to-day behaviors and capabilities. So, while it is concerning that company leaders scored lower in our surveys than operational staff on our privacy pillars, I’d be even more worried if they scored higher, because when only the leaders think about privacy, it tends to get reduced to mere compliance — aka box-ticking to fulfill legal obligations — and the cognitive behavioral part of corporate culture is neglected. Yes, a privacy culture must encompass metacognitive capabilities, and that requires the tone to be set from the top, at the CEO and board levels. But culture is never all top-down, so the real work of testing and detecting vulnerabilities within your labor force has to happen from the bottom up.

My final word of advice is: zero trust. Some say, “Trust first, then verify.” But the more connected we are, the more vulnerable we are, so it seems like adopting a zero-trust mentality is safest. Stop thinking of privacy in a separate compartment. As humans make more and more privacy decisions every day, if we can educate and equip them with adequate privacy tools, we can enhance cybersecurity by default.

MORE INFO: “Insights on how data privacy officers can build a corporate privacy culture” by Tawfiq Alashoor, Maheshwar Boodraj, André Quintanilha, Sabrina Palme and Hussain Aldawood. MIS Quarterly Executive (2025).

WATCH: The webinar “From humans to machines: the keys to secure digital transformation,” featuring Tawfiq Alashoor with cybersecurity specialists Abdulrahman Alsafh and Jessica Buerger, is available for Members of the IESE Alumni Association to watch on demand here.

This article is included in IESE Business School Insight online magazine No. 171 (Jan.-April 2026).

READ ALSO:

How to save a life: medical data donation in an age of privacy concerns

Beware of digital zombies: How to manage the threats posed by your online activity