IESE Insight

4 steps for companies to fold UN Sustainable Development Goals into their strategies

Closing the science-practice gap in addressing the SDGs.

By Pascual Berrone and Joan Enric Ricart

The 15-year race to meet the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030 is more than half over. With the clock ticking, it’s more urgent than ever for companies to make the goals their own, prioritizing what’s relevant to their strategic agendas and their contexts, and then coming up with collaborative, innovative ways to achieve them.

That may seem a tall order. The sheer number of SDGs — 17 global goals in total, with 169 accompanying action targets — overwhelms. And then there’s the societal sweep of the goals: from eliminating global poverty to forging a peaceful and just world, from reversing climate change to attaining gender equality and full employment.

Yet if there’s any hope of making progress toward the goals, companies must do their part. How? To understand best practices, we closely reviewed practical guidelines produced by organizations such as McKinsey and PwC, as well as articles in leading management journals.

We found that while the practical guidelines offered valuable real-world experience and general instructions, they often lacked the theoretical and empirical wisdom of management research. The more than 100 academic articles published over a decade, meanwhile, were rigorous and important but had not effectively translated into actionable insights.

Thus, we set out to close this science-practice gap, creating an implementation protocol for companies that integrates academic knowledge and practical frameworks to offer a scientifically informed, process-based framework for SDG adoption.

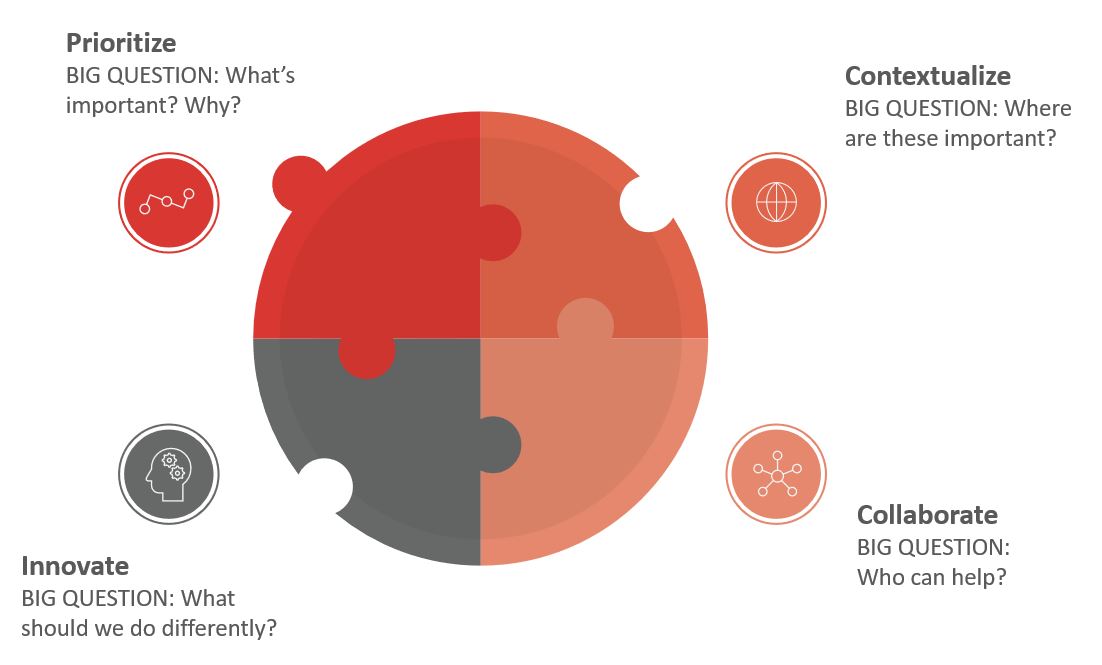

The four-step process for companies

The four-step process asks companies to prioritize, contextualize, collaborate and innovate. Here’s how:

1. Prioritize. To begin, corporate leaders must identify the SDGs that are most relevant to the strategic goals of their company. Beyond alignment between SDGs and the firm’s core activities, relevance also may be rooted in the personal values of decision-makers or in the saliency of a social issue in the place where a company operates. For managers, understanding the links between SDGs and core activities is crucial, since adopting an SDG may affect entire systems and create synergies or trade-offs within organizations.

Prioritization is essential because no company can make meaningful impact on all of the goals; indeed, for some very specific companies, none of the goals may be particularly germane. The complexity of the SDGs means they involve multiple actors, activities and locations. Pursuing too many SDGs runs the risk of diluting resources, and employee commitment and engagement tend to wane without a meaningful focus.

The idea of trade-offs is important. Aligning business objectives with societal needs may lead to tensions and contradictions that managers must embrace rather than ignore. In optimizing scarce resources, managers will have to explore, choose and balance the multiple and sometimes conflicting demands of stakeholders, with a view to the long term.

2. Contextualize. Next, companies must situate SDGs within their geographic and industrial contexts. This allows them to reframe the goals from global calls to action to contextually relevant, manageable targets. Without this reframing, the goals can seem symbolic rather than practical. In addition, some SDGs — gaining access to potable water, for example — are relevant in some communities and not in others. Localizing SDGs helps motivate many managers to achieve them, and allows them to visualize their firms making incremental progress toward specific goals. It also improves stakeholder engagement.

The reframing may also be at an industry level, which enables managers to translate the SDGs into manageable activities while expanding the scope beyond firm-specific actions. For example, a beverage company may add the goal of access to clean water to its strategies, working alongside other industry players to make this happen.

Research shows that contextualization does not necessarily eliminate the trade-offs between the social, environmental and economic. It does, however, help decision-makers to visualize these trade-offs more clearly and to better understand how their choices will impact their community and their industry.

3. Collaborate. Underlining the importance of collaboration, SDG Goal 17 is specifically Partnerships for the Goals. Again, the complexity of the SDGs exceeds the reach of any single organization and unilateral approaches will fail to make a dent in society’s grand challenges. In addition, multiparty collaboration makes better use of common resources and shared technology when addressing SDG-related issues.

That means companies must work alongside multiple organizations and stakeholders — including the public sector, other companies, multilateral institutions and various civil society actors — to make more impactful progress on mutual goals. Public-private partnerships may be particularly fruitful, since they may address governmental and market failures by combining resources and developing complementary capabilities to address social needs.

For many companies, this collaborative effort will require a shift in thinking from managing stakeholders to partnering with them, from confrontational stances (with, for example, NGOs) to relational ones. Part and parcel of this is a move from organization-focused viewpoints to issue-focused viewpoints, and a willingness to engage with actors that managers may not be accustomed to dealing with.

4. Innovate. Innovation here refers to rethinking business models rather than inventing new technologies. Since business models are built on the choices and activities that define the logic and modus operandi of a firm and how it creates value for stakeholders, innovation implies changing the nature and direction of those choices to ensure that their consequences align with SDGs.

Business model innovation (BMI) will include developing a broader and more inclusive notion of profitability, which takes into account the costs and benefits of leveraging environmental, social and economic resources. It will mean altering current business practices while adopting new ones built on a novel logic of societal engagement. At the same time, firms will also need to find novel solutions that use fewer inputs and cleaner technologies.

The level of disruption from BMI will vary widely, depending on the company. For some, incorporating an SDG into strategy is a win-win, and the social benefits of the SDG will align with the firm’s economic benefits. For others, there will be trade-offs to overcome (e.g., lower margins because of a greener, more costly input). And for others, which we call hybrid organizations, the trade-offs will be constant (such as a fossil fuel company going green). These organizations will juggle the often contradictory demands of the market, the environment and society.

It should be noted that these four stages are not necessarily linear. Innovation may lead firms to realize that their priorities are different, or that their industry context has shifted. As they craft their SDG strategy, leaders should be prepared to revisit the different steps.

The SDGs were adopted in 2015 and are meant to be arrived at by 2030. But according to a 2023 UN report, only 15% of the goals are on track; 48% are moderately or severely off track; another 37% have stagnated or regressed.

Time is quickly running out. The moment for companies to prioritize, contextualize, collaborate and innovate, making SDGs part of their corporate strategies, is now.

At a glance:

READ ALSO: All about cooperation, collaboration and partnerships