IESE Insight

Common ownership: implications for competition and markets

José Azar explains his research on common ownership and labor market forces, and the surprising implications for M&As, airline ticket prices and more.

The rise of common ownership — where the same large asset managers are major shareholders in many overlapping companies — is clear to see, if you know where to look. It is especially visible in the growing power of the Big Three: BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street, which together control trillions of dollars in their funds. This matters because common ownership has real implications for competition and markets.

José Azar draws from his award-winning research to help us understand some key forces in play.

Tell us about the beyond in the title of your recent paper “Beyond the target: M&A decisions and rival ownership,” published in the Journal of Financial Economics.

About four years ago, Miguel Anton, Mireia Giné, Luca Lin (IESE PhD) and I took a new look at a long-standing question: why do so many mergers seem to end up as bad deals for the acquirer?

The M&A literature offers possible explanations. Maybe the top managers are overconfident; or they are empire-building, essentially not acting in the interest of the shareholders, so that they can run bigger firms.

And then there was an interesting 2008 paper by Gregor Matvos and Michael Ostrovsky (“Cross-ownership, returns and voting in mergers”) that considered cross-ownership of both the acquirer and the target of the merger — acknowledging that shareholders in the acquirer may recoup at least part of what they are losing if they are also shareholders in the target. But soon after, another paper came out showing that cross-ownership in the acquirer and the target is simply not enough to explain what’s happening.

My IESE colleagues and I decided to look beyond both the acquirer and the target, hence our paper’s title. Consider: when two firms merge, a classic economic model has it that the merging firms lose value unless efficiencies are created. At the same time, the non-merging firms in the same industry can benefit. This is known as “Cournot’s merger paradox.”

In simple terms, suppose you have five firms in an industry. If two of those five firms merge, you are left with just four. Those four can be more profitable, sharing the market four ways. But is the merger good for the two firms that merged? Before, they were two firms out of five, and now they are just one out of four, essentially shrinking in size.

Here is where common ownership comes in. If the merging companies’ shareholders have, in their portfolios, other firms in the industry, then they could actually benefit from their rivals’ gains.

Could you give us an example?

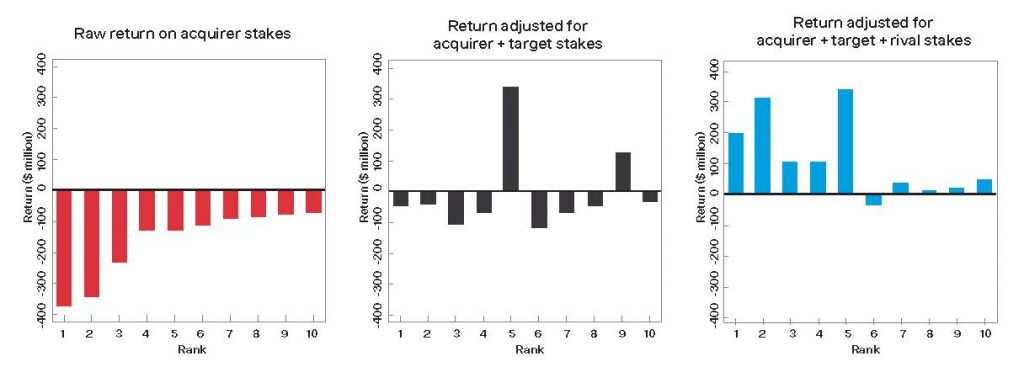

Take Microsoft’s acquisition of LinkedIn. Back in June 2016, the tech giant announced it would acquire LinkedIn for $26.2 billion. In a matter of just three days, right around the announcement, Microsoft lost 1.46% of its value. That 1.46% may not seem like a lot until you consider that Microsoft was worth over $400 billion at the time. So, losses for Microsoft’s 10 largest shareholders were considerable, ranging from $72 million to $373 million in trading. In our paper, we show this in the figure below, in red.

What about cross-ownership? It turned out that nine of these top 10 shareholders of Microsoft were also shareholders of LinkedIn, whose share value jumped a heady 45.97% on news of the deal. That said, for those top shareholders, only two were able to offset their Microsoft losses with the gains from LinkedIn. That’s shown in the figure below, in black.

And now we get to the main point of our paper. Nine of Microsoft’s top 10 institutional shareholders enjoyed a portfolio boost, thanks to their ownership in rival firms within the same industry. If the industry benefits from a merger, those wealth effects matter. Consider this: among Microsoft’s top 20 non-merging industry rivals (that is, the biggest firms within its industry, based on market capitalization), 15 of them gained in value during the same three-day window around the merger announcement, and these gains were more than enough to make up for losses in Microsoft’s value. That’s the final graph, in blue.

| Returns in Microsoft’s acquisition of LinkedIn These three figures show the announcement return to Microsoft’s top 10 largest shareholders (ranked by shares with voting power held) during the (-1,+1) window around the announcement of its acquisition of LinkedIn in 2016.  |

Zooming out from this single example, in our paper we analyze a sample of 1,800 horizontal mergers of public firms from 1988 to 2016 to understand how often shareholders benefit from M&As when ownership stakes in industry rivals are considered.

In sum, we find that it is fairly common that ownership stakes in industry rivals compensate for losses in the acquiring firm. We find this for nearly a third of acquirer shareholders.

Rival ownership doesn’t explain all bad deals, and CEO overconfidence may still be a factor, but it can help us understand why, in a significant number of cases, shareholders don’t vote against deals that are likely to destroy value.

What else on common ownership is in your research pipeline?

I’m working on another paper with Xavier Vives on common ownership called “Revisiting the anticompetitive effects of common ownership,” which looks at data from the airline industry, particularly the pricing for consumers, with a new focus.

This paper differentiates two types of common ownership: intra-industry (i.e., cross-ownership within an industry) and inter-industry (i.e., cross-ownership that spans many industries) as seen with the major index funds, and especially the Big Three.

For example, in the airline industry, if United and Delta have similar shareholders, that’s intra-industry ownership. If United is owned by broad-based shareholders who have stakes in many non-airline firms and/or the S&P 500 index, that’s inter-industry common ownership.

Based on the theoretical work that we have done in this area (see “General equilibrium oligopoly and ownership structure,” published in Econometrica), inter-industry should be associated with lower airline prices for consumers, and intra-industry should be associated with higher prices.

Why did you look at airlines here?

A few years ago, I published a paper with Martin Schmalz and Isabel Tecu, “Anticompetitive effects of common ownership,” which attracted a lot of attention. (See “Why the presence of common shareholders in rival companies looms as a threat” for a summary.) This paper found higher prices on airline routes with higher intra-industry common ownership. This raised some antitrust questions.

Now, we are retesting that work in light of our Econometrica paper, which means we are distinguishing intra- and inter-industry common ownership for the first time with this airline data. And the general equilibrium theory holds: more inter-industry common ownership is actually associated with lower prices.

It’s interesting that our motivation for the paper may have come from the rapid rise in the Big Three, but the effects we documented in our previous paper were coming from the other, less diversified common owners, not the Big Three. So, don’t blame the Big Three for higher airline prices!

Still, as inter-industry common ownership grows, our general equilibrium framework points to workers’ wages and employers’ labor-market power as potential problem areas. What will the effects on workers be if common ownership continues to grow? That is one line of research we are working on now.

Our theoretical Econometrica paper puts everything together — monopsony, product markets, common ownership and more. We look at airline data to understand common ownership’s effects on pricing, but we also know you cannot just isolate one market: all markets must be considered.

So, your new paper helps explain your “general equilibrium oligopoly” paper? Because we could use some further explanation.

(Laughs.) Yes, that was probably the hardest paper I ever worked on. I really learned a lot by doing it, but it took me a few years to process all the messages. What this theory predicts seems very counterintuitive: that diversified common ownership spanning the whole economy should reduce product market markups. It’s great to work on a paper that makes this prediction and then test it to find that it really works!

Tell us about another paper you have written with Liudmila Alekseeva (IESE PhD), Mireia Giné and Sampsa Samila, along with Bledi Taska. What’s the message of “The demand for AI skills in the labor market”?

In that paper, we document a huge increase in employers’ demand for AI skills, and we also document the wage premium offered for those AI skills. On average, there is an 11% wage premium for job vacancies that explicitly require AI skills. We even see the AI premium for job openings within the same firm. Our data tracks through 2019, but I would say, by now, demand and wage premiums are probably even higher.

READ ALSO: AI is increasing demand for managers and changing their skill sets

This article is published in IESE Business School Insight No. 162 (Sept.-Dec. 2022).