IESE Insight

The Demographic Challenge

Rethinking healthcare, pensions and migration for an aging world

Welcome to our report on Demographic Change

By Nuria Mas

Demography is one of the few forces that allow us to anticipate the future with a high degree of confidence, because it is based on hard data, and here the message is unequivocal: we are transitioning to a world characterized by slower population growth and rapid population aging.

Across most advanced economies, fertility rates are below replacement levels, while life expectancy continues to rise, averaging 84+ years not just in Western European countries like Italy, Spain and Switzerland, but also in Asian countries like Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore and South Korea. This trend is not cyclical or temporary but structural and global.

This has implications for economic growth, which is driven by two fundamental forces: the size of the working-age population and how productive that population is, with the former conditioning the latter, which is, in turn, decisive for a nation’s prosperity.

Aging populations put pressure on systems built for different times. Concerns around pensions, healthcare and labor markets are well founded, and without urgent reform, their sustainability is in question, warns Javier Diaz-Gimenez. Encouraging higher fertility is insufficient on its own: pronatalist policies, where they have been tried, have not proven successful, and it takes a very long time to reverse multigenerational demographic declines.

Migration may be an answer for certain sectors facing acute labor shortages. However, as Douglas Massey, in conversation with Marta Elvira, and Joan Monras both point out in this report, migration is no silver bullet either. It must be managed well from a long-term socioeconomic perspective.

In Spain, for example, the migration flows needed just to maintain the current ratio of old-age to working-age populations would amount to around a million migrants a year for the next 30 years. Can such migratory flows be managed in ways that do not add to the challenges already facing public services?

Healthcare is illustrative of the challenges ahead. As populations age, demand for healthcare rises sharply. But it’s not just older people with chronic conditions putting pressure on the system — doctors also get older, with an EU average 1 in 3 doctors due to retire in the next 10 years. Who will replace them? Where will they come from?

This IESE Business School Insight report explores these issues — not just to attest to the challenges but to present the opportunities that exist, if we are willing to reorganize our societies, labor markets, healthcare and pension systems, and foment productivity, which holds the key to preserving growth and living standards.

Companies will be at the heart of this transformation. The best response to aging is not cutting benefits but extending active lives and improving productivity. This requires firms to design jobs and career paths for all stages of life, while workers will need to reinvent themselves multiple times over longer careers. This may also imply rethinking traditional wage trajectories and accepting that incomes will not always rise monotonically over a lifetime.

Talking about demography and longevity is not about managing decline. It is about preparing for a predictable transformation — and turning one of the defining trends of the 21st century into a source of resilience, innovation and sustainable growth.

Sustaining healthcare under demographic strain

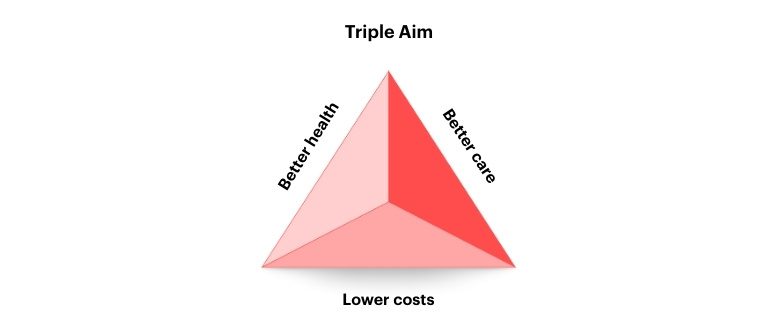

Transforming healthcare to meet demographic challenges requires delivering on three objectives simultaneously — better health, better care and lower costs — what’s called the Triple Aim. This model has already proved successful in a pilot in Catalonia for patients with complex chronic conditions.

In addition, we need to extend active lives — working, volunteering, caregiving — to improve physical and mental health, reduce chronic disease and allow people to contribute to society for longer.

Preventing pensions from running dry

Think of pensions as a giant water reservoir. Low birth rates act like a prolonged drought. Even though less water fills the tank, more people keep drawing from it for longer. To keep it from emptying, we must manage these key valves, among others:

- Raising the retirement age.

- Linking pensions to actual lifetime contributions.

- Adjusting indexation to reflect the system’s financial balance.

There are more people than ever living outside their country of birth, but they are not distributed evenly around the globe. Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, Asia and Eastern Europe are the main regions of origin, while the United States, Canada, Europe, Australia, New Zealand and the Persian Gulf states are the main destinations.

Migration: 4 key predictors

According to award-winning sociologist Douglas Massey, 21st century migration flows can be understood and even anticipated by examining these key factors:

- Demographics. Fertility rates and population growth influence migration patterns. A population’s age structure is a key determinant because people aged 18 to 30 are those who most often migrate for work.

- Economics. GDP per capita, job availability, inflation rates and currency devaluations provide strong material incentives for migration for purposes of income maximization or risk diversification.

- Climate. A region’s exposure to climate-related hazards, as well as its capacity to cope with those hazards in life-supporting areas like food, water and habitat, will influence the decision to leave or stay based on questions of survival.

- Governance. A region’s capacity to govern effectively, based on human rights and the rule of law, makes for stable, peaceful societies with less reason to leave. The more political instability, societal divisions/grievances and lethal violence, the more likely there will be human flight/brain drain.

This report forms part of IESE Business School Insight online magazine No. 171 (Jan.-April 2026).

15% off with the code INSIGHT15