IESE Insight

What kind of innovation do you want to create?

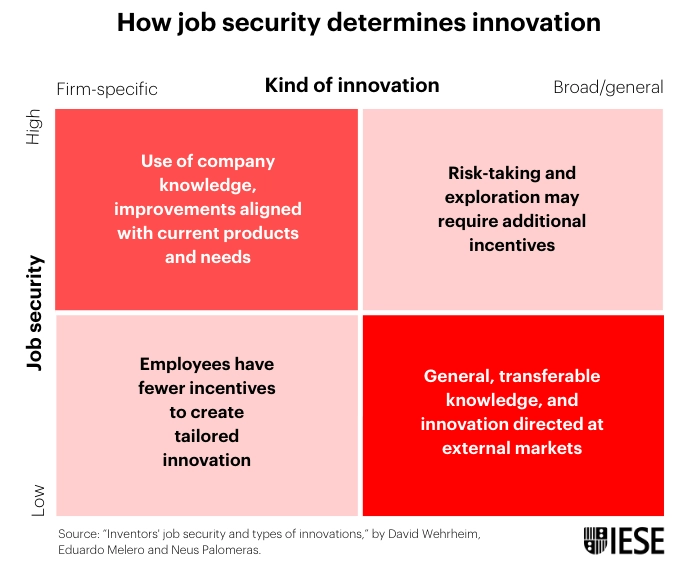

Managers: Do you need firm-specific improvements or out-of-the-box thinking? Job security plays a bigger role than you may realize.

All firms want innovation, but they don’t always tightly define the kind of innovation they need or the workforce best suited to deliver it.

Let’s consider two engineers with similar skills, both working on similar problems.

Anjali works for a company with strong job protection. She expects to be there for the long term, which means she invests time mastering the firm’s particular technologies and building on them, and she chooses projects that reinforce their existing strengths. Her innovations aren’t radical, but they are aligned with what the company needs in the short term.

Meanwhile, Becky works at a company with weak job protection. She knows that a single failed project could jeopardize her position. She therefore chooses problems that build broad, transferable expertise and pursues ideas that would appeal to many employers. Her ideas might fit less tightly with her firm’s core, but they can potentially be more radical, because they break with that firm’s particular culture.

Innovation is about testing new ideas that often fail. It’s a commonly held idea that job security gives innovators the peace of mind to take these risks — security fosters discovery.

I add some nuance to this idea in a paper with Eduardo Melero and Neus Palomeras. Our findings show that job security also has an effect on the kind of innovation firms get.

Comparing R&D output by labor policy

We studied employee inventors at publicly traded U.S. firms, during a period when employee-friendly “wrongful discharge laws” were being passed, between the 1970s and 1990s. We focused on established companies, where patents could be clearly linked to employers, rather than startups or private firms. Overall, we tracked 82,000 inventors who were granted patents at U.S.-based publicly traded firms.

Wrongful discharge laws make it harder for firms to fire employees without a valid reason. They were adopted at different times across different states, meaning we could compare inventors before and after their job security increased, as well as comparing results between states with different laws.

In short, we looked at what happened to innovation when employees had legal protection against firing. It’s also important to note that we looked specifically at R&D professionals — people hired to innovate. Among general employees, job protection has been shown to increase optional innovation because workers feel protected from failure.

But for employees whose job is innovation, it looks a little different. As the examples above would suggest, the first effect of job security was its impact on workers’ incentives to invest in firm-specific skills. We found that the projects these inventors undertook changed.

Consider a senior engineer leading product development at a consumer goods firm. One option is to pursue patents that tweak and build on proprietary equipment, internal know-how and past products. These inventions are valuable inside the company but of limited use elsewhere. They also require employees to study and immerse themselves in the specifics of the firm, perhaps to the detriment of building a portfolio that would impress more on the job market.

Through an analysis of the patents granted in states with wrongful dismissal legislation, we saw that inventors with high job security were more likely to settle into their firms’ processes, sacrificing wider employability and pursuing incremental — but often highly relevant — innovation for their employer.

Those who were less protected were more likely to rely on broad, general-use technologies and think a little more outside of their particular box. Though there’s no guarantee of radical innovation, our patent analysis showed that novel or disruptive creations were more likely in this setting.

It’s a trade-off: what does it mean for managers?

Job security shapes the kind of innovation you get, not just how much.

Managers know that both incremental and disruptive innovation are valuable. Knowing that stable employment encourages deeper use of firm-specific information is important; it can lead to developments that target your specific needs and clients. If this is the innovation you’re trying to develop, it may be worth building assurances of job security into your hiring processes and workplace culture, if they’re not already protected by legislation.

And if you want to encourage breakthrough innovation? Managers in areas with strong workplace protections may need to add measures to counter these effects, such as job rotations or external collaboration, rewarding novelty or just signaling from leadership that risk is appreciated and won’t be penalized.

What we’re not saying: Get rid of workforce protections.

What we are saying: Understand how they shape innovation, and plan accordingly.

ALSO OF INTEREST:

How US-China trade rivalry became a trigger for innovation

No, honoring sunk costs is not always irrational

“Stop doing dumb stuff!” Patty McCord on reinventing the rules of work at Netflix