IESE Insight

Top team behavior for winning results

Does your C-suite demonstrate “teamness”? These are the competencies for boosting positive energy that will ripple throughout the team.

Imagine the top management team (TMT) of a large pharmaceutical company. Patents are due to expire, government regulations are changing, and insurance companies are discussing systemic reforms. Such challenges cannot be faced by simply dividing them up between different members of the C-suite. To perform well in turbulent environments, you need to harness the synergies of a well-coordinated, well-functioning team.

My research is dedicated to understanding how top managers can develop and maintain high-performing teams.

The focus on teamwork may seem at odds with the widespread notion of leadership as an individual act — lone heroes when things go right, renegade villains when things go wrong, or what Donald Hambrick once called “semi-autonomous barons.” This is a mistake. Research indicates that a lack of TMT unity can have serious organizational consequences, from lower quality strategic decisions to decreased financial performance.

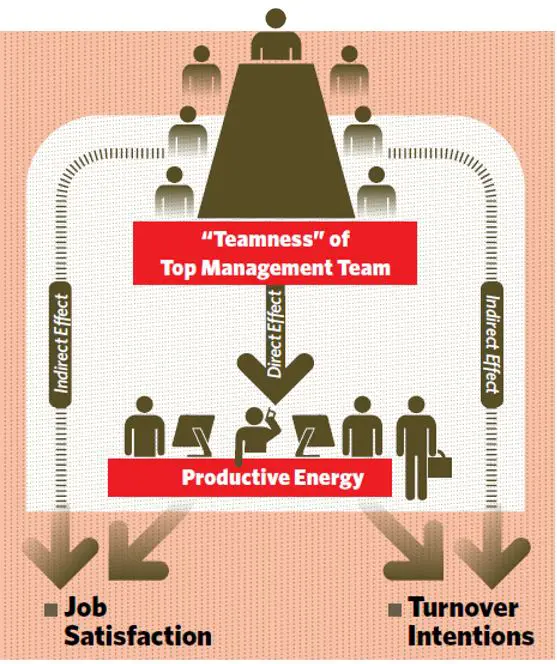

The reverse is also true, as my own research shows. When teams take targeted actions to develop certain competencies, they can achieve positive results, boosting the organization’s productive energy and increasing employee wellbeing.

What are the implications of top management “teamness”?

This question was the start of research I did with Heike Bruch and Simon B. De Jong. We studied 191 TMT members and 5,048 employees from 63 small and medium-sized organizations.

Some might argue that what goes on behind the closed doors of the C-suite is of no concern to employees nor do they necessarily care. But this is not true. TMT behavior does leak out, and employees are highly interested in what they hear on the grapevine.

Given that teamwork is such an inherent part of the design and culture of modern organizations, we expected that employees would be highly sensitive to their TMT’s “teamness” and would use it as a model for their own behavior.

We found that when a TMT modeled a high level of “teamness,” middle managers and other employees were more excited about their work, they could better focus their thoughts on their work, and they worked together more cooperatively.

In other words, these organizations had a higher level of productive energy, which has been directly linked to higher organizational performance.

So, even though few employees may have direct TMT contact, TMT behavior does ripple down throughout the organization. What starts as the opinion of a few may quickly infect collective behavior.

Given this, the extent to which TMTs present a united front can have huge ramifications for the overall work climate, conditioning whether lower-level managers and employees freely cooperate with one another, function well as teams, communicate openly and are clear about what needs to be done.

When employees have positive impressions of their TMT, they have greater cognitive capacity to focus on their work, dedicate more energy to constructive thinking, experience fewer hassles when solving work-related problems and generally feel more uplifted in the work they do.

Conversely, TMTs that display fragmented or inconsistent behavior trigger negative emotions, such as frustration, irritation and anger over the lack of direction and unity.

These feelings are exacerbated when TMTs say different things at different times to different people. Inevitably, employees will begin to perceive conflicts among the multiple goals they are supposed to achieve. Eventually, they become confused as to which goals are the most important and what they must do to achieve them. This results in a loss of energy, not to mention all the time wasted on idle speculation as to the direction in which the TMT actually wants to take the organization.

So, if TMT unity is so important, not only for the smooth functioning of the C-suite but also for the operational success of the entire organization, then how can senior managers achieve such unity?

3 competencies to ensure smooth functioning of the C-suite

1. Collaborative behavior

TMTs that openly share information and opinions, and carry out their work collectively, outperform TMTs that do not.

Multiple studies support the finding that behavioral integration has important knock-on effects for the quality of decisions made as well as organizational performance. Openly sharing information and opinions within the TMT should be strongly encouraged.

The alternative is that TMT members operate in separate spheres without much contact or information sharing. They may also seek to influence decisions by politicking, and thereby inhibit true collaboration.

Ask yourself:

- What is the level of “teamness” in my TMT?

- Do the members of my TMT function as a behaviorally integrated unit or as a fragmented group of “semi-autonomous barons”?

2. Effective information exchange

Functioning as a behaviorally integrated unit implies that TMT members need to spend time communicating with one another.

Admittedly, this can be challenging, given the multitude of responsibilities resting on the TMT’s shoulders, which limits the amount of time and energy TMT members are able to devote to each task.

However, information exchange is not so much a question of frequency of communication as it is about quality. In fact, one study suggests that very frequent communication in the TMT may mask time-consuming conflicts and ineffective decision-making processes, and relates to lower organizational performance.

Instead, TMTs should try to focus on optimizing the quality of their communications during the moments when they do convene.

Ask yourself:

- Do we have the right communication structure in place to ensure adequate information exchange?

- Do we make optimal use of our moments of face-to-face interaction?

3. Joint decision-making

Another key facet of decision-making (besides effective collaboration and quality communication) is the TMT’s ability to make decisions jointly. And key to that is the TMT’s ability to handle conflict.

Conflict refers to disagreements among TMT members about the task being performed, including differences in viewpoints, ideas and opinions.

As counterintuitive as it may seem, conflict between TMT members can actually be beneficial. As some research has shown, the more task conflict in the C-suite, the more comprehensive the decision-making process. TMT members’ understanding and acceptance of decisions also increases, as does their commitment to implement those decisions.

When a decision is arrived at jointly — that is, after everyone has honestly grappled with the issues, genuinely listened to all points of view and felt heard — a real sense of unity emerges, as opposed to a forced sense of obligation. In this way, the conflict is dealt with in a healthy manner, and it is not allowed to fester and contaminate the rest of the organization.

This implies that TMTs must also take steps to ensure that differences of opinion do not spill over into bitter personal rivalries.

This requires a high level of trust between TMT members, so that the TMT reaps the full benefits of task conflict while avoiding detrimental relationship conflict. When there is a high level of trust in a TMT, task conflicts stay contained, with discussions focused on matters of content rather than personalized attacks.

Ask yourself:

- Does my TMT leverage the beneficial aspects of task conflict and avoid dysfunctional relationship conflict?

- Which dynamics do I want to optimize or minimize to facilitate joint TMT decision-making?

How to correct disunity outside the C-suite?

TMT unity is not, in and of itself, enough to achieve high performance across the organization. For that, something more needs to happen, as I discovered in this research and this research with co-authors Mariëlle G. Heijltjes, Ursula Glunk and Robert A. Roe.

During our observations of board meetings of the TMT of a Dutch organization, the first thing that struck us was how much they worked as a high-performing team. Their discussions were intense but task-related, with few interpersonal conflicts. Each member openly exchanged information and opinions, eschewing political games or backroom wheeling and dealing. The TMT even held special monthly sessions to reflect on its functioning and processes, as well as annual three-day retreats for strategy building. In short, this TMT was everything you would want it to be.

In spite of this, TMT members were struggling to get their strategic decisions to work in the organization. From our observations, it became clear that the source of the problem lay not inside the C-suite, but rather outside it — and more specifically, in the relationships between the TMT and middle managers.

Repeatedly, TMT members would vent their frustration about middle managers dragging their feet, digging in their heels or even intentionally sabotaging the TMT’s carefully laid plans.

As we have since discovered, these are common complaints in many organizations. TMTs have the formal power to steer their middle managers, but to do so effectively, they need to be experts in orchestrating these relationships.

Which competencies are needed for middle managers?

For optimal organizational outcomes, middle managers make up the other half of the equation. They create alignment — synthesizing information, championing alternatives and selling ideas — and they exert a strong influence on organizational performance, since they and their own team members are the ones responsible for putting the TMT’s strategies into action.

When middle managers lack commitment, they can create obstacles or even sabotage the TMT’s plans. This often occurs in situations where middle managers’ self-interests are at stake, when they perceive a strategy to be flawed or when they are incapable of implementing it.

To build commitment, top managers must win the trust, or at least the compliance, of middle managers.

This is easier said than done. There are risks on both sides: the TMT must rely on middle managers who may represent their unit’s interests more than the organization’s; and middle managers must rely on the TMT who may have interests that put middle managers and their units at a disadvantage.

Since it is impossible for the TMT and middle managers to monitor each other’s movements and actions constantly, their trust in each other becomes vital. Building this trust requires a second set of competencies for TMTs and middle managers alike.

1. Cognitive flexibility

This relates to forms of information sharing characterized by reflecting, reviewing information, taking into consideration different perspectives, being open to hearing each other out, being able to change opinions and developing a broad variety of interpretations.

When cognitive flexibility is high, interactions between the TMT and middle managers are much more productive.

- First, more diverse information is taken into account.

- Second, the complexities of the cause-and-effect relationships inherent in the strategy process will be better understood.

- This, in turn, enables the TMT and middle managers to make clearer sense of the information obtained from the environment.

- Finally, cognitive flexibility increases the creativity with which information is interpreted and the alternatives generated. This may induce cognitive shifts in interpretation that facilitate positive change.

The TMT and middle managers can achieve greater cognitive flexibility by explicitly asking for information, providing both solicited and unsolicited information, and critically reviewing that information.

Above all, both parties must learn not to let their inherent power differences inhibit the open sharing of information.

Ask yourself:

- To what extent is cognitive flexibility apparent during information sharing between the TMT and middle managers?

- How can I increase it?

2. Integrative bargaining

TMTs and middle managers are constantly engaged in a myriad of influence processes toward each other.

TMTs exert influence on middle managers in an effort to generate commitment and understanding of the corporate strategy, as well as instilling in middle managers a strong sense of organizational recognition, ownership and motivation for decision implementation.

For their part, middle managers seek to gain resources for implementation, have their input acknowledged and get new ideas accepted.

Mutual influencing is a two-way street: One party tries to influence the other, who articulates a reaction to that influence attempt, with both parties having to reach a satisfactory compromise.

Either party may seek to influence and be influenced by the other. In this dance, the collaboration between TMTs and middle managers sometimes resembles a multiparty, mixed-motive negotiation, due to the asymmetry of information, influence and interests.

The competency of integrative bargaining can be a helpful way for TMTs and middle managers to reach cooperative arrangements in which both parties create shared value.

Integrative bargaining improves implementation quality for several reasons:

- First, it takes the interests of both parties equally seriously. If middle managers perceive an alignment between their interests and the strategic decision being taken, then they will be more committed to the implementation.

- Second, middle managers usually have better and more realistic insights into what effective implementation entails. By taking their input into consideration, integrative bargaining should result in a better allocation of resources.

- Last but not least, integrative bargaining can yield more creative ideas and solutions, for the simple reason that achieving a win-win result by nature entails more dynamic thinking than merely imposing TMT mandates on middle managers.

Ask yourself:

- To what extent is the mutual influencing process with middle managers characterized by integrative bargaining?

- What could I do to increase it?

3. Use every contact as a window of opportunity

Heavy restrictions on everyone’s time can make contact between TMTs and middle managers rather sporadic. This is an inescapable fact of modern working life, but accepting there will be a scarcity of contact need not define predetermined outcomes. Instead, both parties must make a concerted effort to overcome such obstacles and make the most of their rare interaction opportunities.

Contact may be formal, through scheduled meetings with fixed agendas and protocols. But there is also informal contact, through phone calls and spontaneous encounters in hallways or before meetings.

Any contact can serve as an opportune moment to discuss recent developments, and to coordinate and adapt behavior for the periods when there is no contact.

This is especially important bearing in mind my earlier remarks concerning the asymmetrical relationship between TMTs and middle managers by virtue of their different organizational functions and the diverse ways in which they interpret organizational events.

If we accept that information exchanges are necessary for the smooth running of the organization, in terms of the quality of strategic decisions and their implementation, then both parties will need to pursue and leverage every contact as an opportunity to ask for, give and review information on a periodic basis.

Ask yourself:

- When are the moments of contact between TMTs and middle managers?

- Are they formal or informal, planned or spontaneous, short or long?

- How can I use these moments of contact more effectively?

Dimensions of participative leadership to measure success

In developing all these competencies, the aim is to create a more participative form of leadership that values information, seeks frequent and effective interaction to obtain information, and uses that information as a basis for strategy.

Granted, participative leadership does carry risks. It increases the TMT’s vulnerability by reducing its control over the outcomes of strategic decision-making. By extension, it increases the chances of middle managers abusing their power.

However, such risks are significantly outweighed by the potential benefits. These include:

- improved cognitive flexibility;

- a more balanced mutual influencing process;

- greater use of creativity in the pursuit of integrative solutions;

- more frequent and more valuable interactions overall between the two levels of management.

Other studies that I have done among the middle managers of hundreds of international firms (summarized in my book) revealed five dimensions along which TMTs could measure their success at achieving this kind of participative leadership. When it comes to the first three — company results, strategic leadership and TMT unity — some companies may feel that their work has been done. Yet can they say the same when it comes to the other two dimensions of connectedness and moral leadership?

As we found, the middle managers regarded company results as a less important aspect of TMT performance, while they had much higher expectations for the TMT’s moral leadership, which they felt was wanting.

Such discrepancies should serve as a timely reminder of the need to better understand and take into consideration the feelings and opinions of strategic stakeholders such as middle managers.

To do that, TMTs will need to stop seeing themselves as independent, omnipotent entities, and begin looking far beyond the boardroom for solutions to the challenges their organizations face.

If the top management team is able to model the right competencies, there will be positive ripple effects on an organization’s productive energy and on employees’ job satisfaction and turnover intentions as a result.

And as boardroom leaks go, that is worth gossiping about!

This article is published in IESE Insight magazine (Issue 20, Q1 2014).

This content is exclusively for personal use. If you wish to use any of this material for academic or teaching purposes, please go to IESE Publishing where you can purchase a special PDF version of “Top team behavior for winning results” (ART-2499-E), as well as the full magazine in which it appears, in English or in Spanish.