IESE Insight

The sweeping change of net zero emissions

Can the Big Three asset managers — BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street — influence companies to clean up their acts and lower their carbon emissions? Miguel Duro discusses his research on how they do it and why you should pay heed.

In early 2020, before the pandemic hit Europe, climate activists occupied BlackRock's Paris office, accusing the world's largest asset manager of being complicit in climate inaction for not pressuring their portfolio companies to reduce their environmental impact. Is this fair criticism? Miguel Duro shares what his research with IESE colleagues José Azar, Igor Kadach and Gaizka Ormazabal has found. And he explains why the transition to a net zero economy is a trend that no company can ignore.

IESE Insight: What role do the investment giants play in influencing companies on the environment?

Miguel Duro: We studied what impact the Big Three — BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street Global Advisors — had on companies reducing their carbon emissions. We chose to measure carbon emissions as opposed to changes in a firm's environmental score, which could reflect greenwashing rather than actual environmental improvements.

We found that the Big Three were more likely to engage with companies with the highest carbon emissions. In fact, the Big Three focus their engagement on large companies (those with greater potential to have an effect on global carbon emissions) and on those in which they have a more significant stake (and, therefore, a greater capacity to influence).

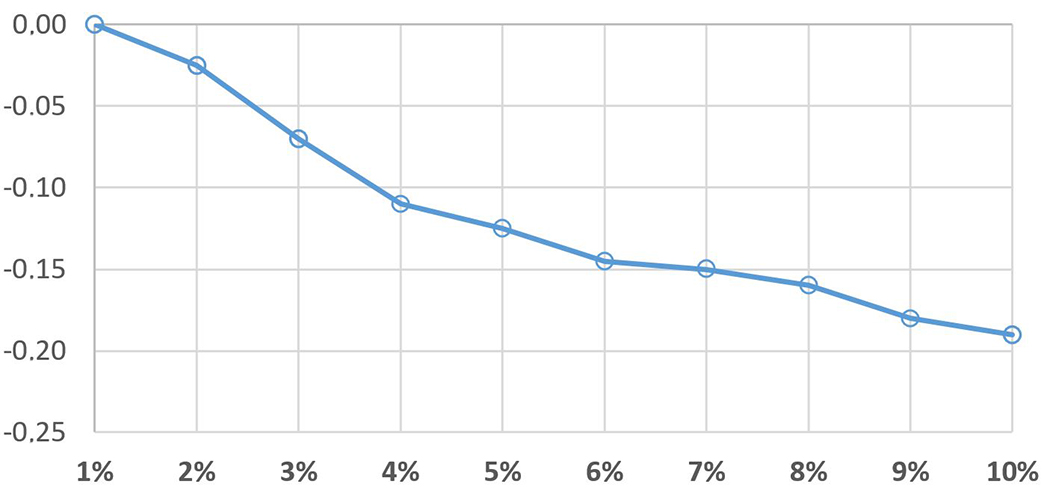

The greater the probability of the Big Three meeting with CEOs, the more likely it was that carbon emissions by the company were lower in the following year. We observed this phenomenon taking effect from a relatively low shareholding of just 3%-4% (see figure 2 below) and intensifying as ownership levels increased, notably since the 2015 Paris Agreement (see figure 1).

Our findings support the thesis that the Big Three do try to influence the most polluting companies to reduce their CO2 emissions.

1. Average reduction in CO2 emissions by companies held by the Big Three.

Source: authors' own.

2. Average reduction in CO2 emissions according to the % of shares held by the Big Three.

Source: authors' own.

II: Yet we generally don't see them using their voting power to do that. Why not?

MD: Shareholders can exercise their power in three ways: voting in shareholder meetings, selling their shares (aka voting with their feet) or engaging directly with the company's top management to express their concerns. The Big Three tend to favor the latter option. As such, to measure their influence, you have to consider their communications with management, not just how they voted.

That said, BlackRock has stated it would use its vote against management where it doesn't see sufficient progress being made, and "will also flag these holdings for potential exit... because we believe they would present a risk to our c

lients' returns."

II: How important is this influence?

MD: The Big Three are the largest institutional investors in the world, by far. Together they control 20-25% of the shares of the S&P 500 and constitute the largest shareholder in 88% of those firms. They own 20% of Citigroup, 19% of JPMorgan Chase and 18% of Apple, to name a few. This puts them in a unique position: When they request meetings with the CEOs of the companies in which they hold such major stakes, those CEOs generally don't say no.

Granted, having such outsized influence over the global economy is controversial. In different studies, my IESE colleagues José Azar, Miguel Antón and Mireia Giné have found that when so many shares of public companies are held by the same few investors, the effects of this common ownership can be deleterious, rewarding CEOs with higher pay even as competition between their firms is reduced, which is ultimately harmful to consumers.

Despite these concerns about the size of their power and reach, this does give the Big Three a decided advantage when it comes to addressing major issues, such as climate change, that require a globally coordinated response.

II: Why not use regulation?

MD: We need global regulation, but the coordination costs are huge. Different sectors interact with each other and contribute to CO2 emissions in different ways and with different intensities, presenting a measurement challenge. This is a point made by another IESE colleague, Valentina Raponi, who shows that the sectorial impact on CO2 emissions in different settings is far from linear, which should be reflected in any environmental modeling framework.

The coronavirus pandemic has made deadly clear the difficulty of globally coordinated action. Leaving it to each country or company to go its own way on climate change would be just as bad, because we all share the same planet and breathe the same air. Even more difficult with climate change is that the true costs may take decades before they are fully known, and the cause-effect relationship is not so easy to measure.

Given these challenges, having large asset managers collectively pressing companies on climate change can serve as a catalyst for change, helping drive regulatory action by governments.

II: What's in it for institutional investors?

MD: Several things. First, the bottom-line implications of non-compliance: "Institutional investors believe climate risks have financial implications for their portfolio firms and that these risks, particularly regulatory risks, already have begun to materialize," according to research published in The Review of Financial Studies.

Second, while some individual companies may resist taking action on climate change because its consequences are not yet real to them in their region, the Big Three, with their multiple holdings around the world, don't have that luxury, so they're more motivated to move everyone in the same direction.

Third, investors are increasingly demanding environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards be met, as highlighted in a report on the rise of socially responsible investing by IESE's CaixaBank Chair of Sustainability and Social Impact. Fund managers need to satisfy the demands of socially conscious customers, especially "to win the soon-to-accumulate assets of the millennial generation, who place a significant premium on social issues in their economic lives," according to a European Corporate Governance Institute Law Working Paper.

Finally, as BlackRock Chairman and CEO Larry Fink notes in his 2021 letter to CEOs, all these moves are not just because the world is forcing us in this direction; instead, he sees the opportunity of a "sustainability premium" in transitioning to a net zero economy. As he explains, companies with better ESG profiles not only outperform others, but within the same industry, from cars to oil and gas, those with ESG profiles perform better than their own industry peers. The more we do this, "the better able you will be to compete and deliver long-term, durable profits for shareholders."

II: What are the lessons for CEOs?

MD: CEOs may understandably be concerned that responding to all these demands may lead them to take their eye off the ball of the business and its owners. But in being the largest representative shareholder, the Big Three are representing the most relevant issues to which management may legitimately respond, knowing they are acting in the common interests of shareholders.

Remember, too, that in addition to representing active investors, the Big Three manage a large number of passive funds, which usually have long investment horizons. Companies with these types of investors (or those willing to attract them) will have an even greater incentive to pursue sustainability goals.

All companies would do well to closely monitor these trends. Concern about the environmental impact of companies is growing, not just among shareholders but among employees, customers and a multitude of other stakeholders in society. It's time for everyone to clean up their acts.

MORE INFO

"The Big Three and corporate carbon emissions around the world" by José Azar, Miguel Duro, Igor Kadach and Gaizka Ormazabal is forthcoming in the Journal of Financial Economics.

The report, "New paradigms in purpose, ownership and engagement" from IESE Business School Insight 155, features more on this topic as well as an interview with Amra Balic, BlackRock's head of EMEA Investment Stewardship.