IESE Insight

Beyond teaming up: how corporate venturing squads work — and where they struggle

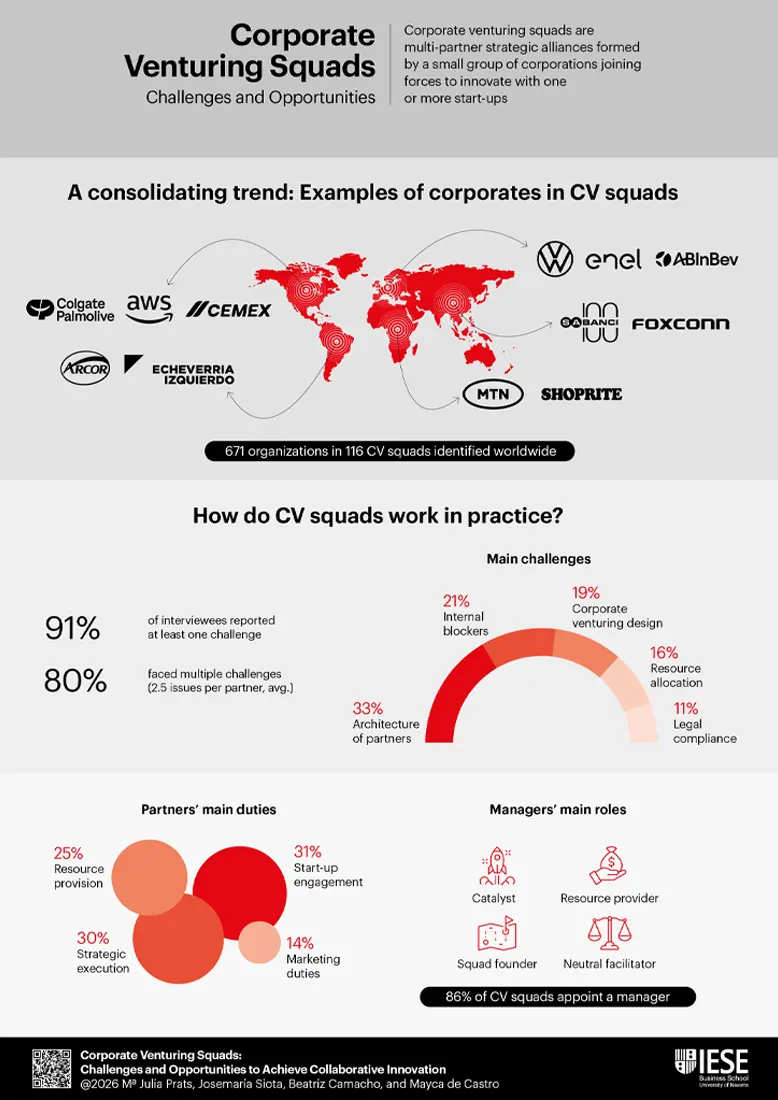

IESE’s latest report on corporate venturing squads reveals how they work in practice and the best ways to manage multiparty frictions to achieve innovation.

As innovation challenges become more complex and systemic, corporations are increasingly turning to corporate venturing squads (CV squads) — alliances in which multiple companies jointly scout, test or invest in startups.

100+ Accelerator, a CV squad that brings together AB InBev, Coca-Cola, Colgate-Palmolive, Danone, Mondelēz International and Unilever, illustrates how even competitors can collaborate, supporting nearly 200 ventures across 40 countries to deliver sustainable solutions in areas such as water stewardship, smart agriculture and circular packaging.

Yet, the success of these CV squads is far from automatic, prompting IESE to study the challenges and opportunities to achieve collaborative innovation in CV squads.

IESE has played a pioneering role in conceptualizing and studying this emerging collaboration model, first in 2020, and then in 2021 research on CV initiatives across Asia, the Americas and Europe. IESE’s dedicated study on CV squads, published in 2023, further mapped what CV squads are and how they are structured.

IESE’s latest report now focuses on how CV squads operate in practice. Developed by IESE’s M. Julia Prats, Josemaria Siota, Beatriz Camacho and Mayca de Castro, with the participation of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) as an ecosystem partner, the new report draws on evidence from 51 CV squads to examine where friction emerges, how challenges vary by squad type, and which cooperation-and-management choices help sustain multicorporate collaboration over time.

CV squads are consolidating as a collaboration model

CV squads are shedding their experimental label. Of the 23 recurring squads tracked in 2023, 16 remain active (70%). Among these, 10 have grown by adding new partners, while the rest either swapped partners without changing size or intentionally slimmed down. This mix of persistence, expansion and smart rebalancing shows that CV squads are evolving into stable, strategic vehicles for corporate/startup collaboration, not just short-lived pilots.

The scale of adoption is also notable. Since the analysis began, 671 organizations across 116 CV squads worldwide have been identified, both active and past initiatives. While this is a conservative, cumulative count, it signals a broad, growing movement, hinting that the real number of squads in action is likely even higher.

The real problem is governance, not innovation

Friction is the rule, not the exception, in CV squads: over 90% of CV squads report at least one challenge, with 80% facing multiple issues at once. Collaborative innovation is, therefore, not about eliminating friction but about anticipating and managing it well.

The most frequent sources of friction in CV squads are organizational rather than technical. The largest single challenge is partner architecture misalignment (33%), followed by internal corporate blockers (21%) and CV design mismatches (19%). Together, these challenges reflect difficulties in aligning partners, decision processes and collaboration models as squads move from formation to execution. Legal issues (11%) and resource constraints (16%) also surface, but less frequently.

When competitors collaborate, friction looks different

The type of friction CV squads encounter varies systematically with their structural configuration. Factors such as squad size, prior collaboration among partners, organizational contact points and the presence of competitors are all associated with distinct challenge patterns.

A counterintuitive pattern emerges when comparing competitor and noncompetitor squads. Collaborations among competitors might be expected to struggle most with coordination and venture design. Instead, the data points in a different direction. Competitor-based squads face higher legal and regulatory friction (30% vs. 7% in noncompetitor squads), while displaying similar levels of partner architecture alignment challenges as noncompetitor collaborations. Meanwhile, noncompetitor squads are more exposed to CV design mismatches (24% vs. 9% in competitor squads) and resource allocation challenges (17% vs. 9%). This contrast suggests that competition often leads to stricter upfront formalization of respective responsibilities, whereas more friendly collaborations leave greater room for ambiguity to surface during execution.

Different squad types bring different needs

CV squads encounter friction, organize execution and choose managers in different ways. Across the six squad types analyzed in the report (scouting forces, scouting platforms, joint proofs of concept, partnerships, coinvestments and joint funds), distinct patterns emerge in the configuration of challenges, partner duties and manager profiles, closely linked to each type’s time horizon and core activity.

Rather than facing a single, generic set of execution problems, squad type serves as a structuring lens for understanding multicorporate collaboration, revealing different coordination logics depending on what squads are trying to achieve and over what horizon. For leaders seeking to scout emerging technologies, test solutions with startups or invest alongside corporate peers, this means that governance and leadership needs vary systematically across squad types, rather than following a single, uniform model. For example, one-shot CV squads report partner-architecture issues more frequently than recurring types.

CV squads organize execution around four core duties

Despite wide variation in structure and ambition, CV squads converge around four core partner duties:

- strategic execution responsibilities (42%)

- resource allocation commitments (27%)

- startup engagement tasks (18%)

- dissemination and visibility agreements (13%)

These recurring duties define how work is divided across partners and where accountability sits. Taken together, they provide an operating backbone for understanding how squads move from intent to coordinated action over time.

The CV manager is a critical enabler

Nearly all effective CV squads rely on a dedicated alliance manager to maintain momentum and alignment (86% appoint one). Management profiles vary systematically by squad type. For example:

- Early-stage or exploratory squads benefit from founder-type leaders who provide vision and energy.

- Recurring, execution-intensive collaborations are best served by catalyzers who coordinate across organizations.

- Investment-led squads, especially among competitors, require neutral managers who ensure fairness, discipline and trust.

Choosing a management profile that is not well aligned with the squad’s configuration can hinder progress, underscoring that execution capacity and coordination credibility, rather than formal hierarchy, are particularly important in how CV squads operate in practice.

CV squads are not always easy to run. But if designed with governance discipline and led intentionally, they can allow companies — even competitors — to share risk, accelerate learning and address innovation challenges that no single firm can solve alone.

ALSO OF INTEREST:

Corporate venturing squads: Teaming up with other corporations to innovate with startups