IESE Insight

Three trends that will change how you manage

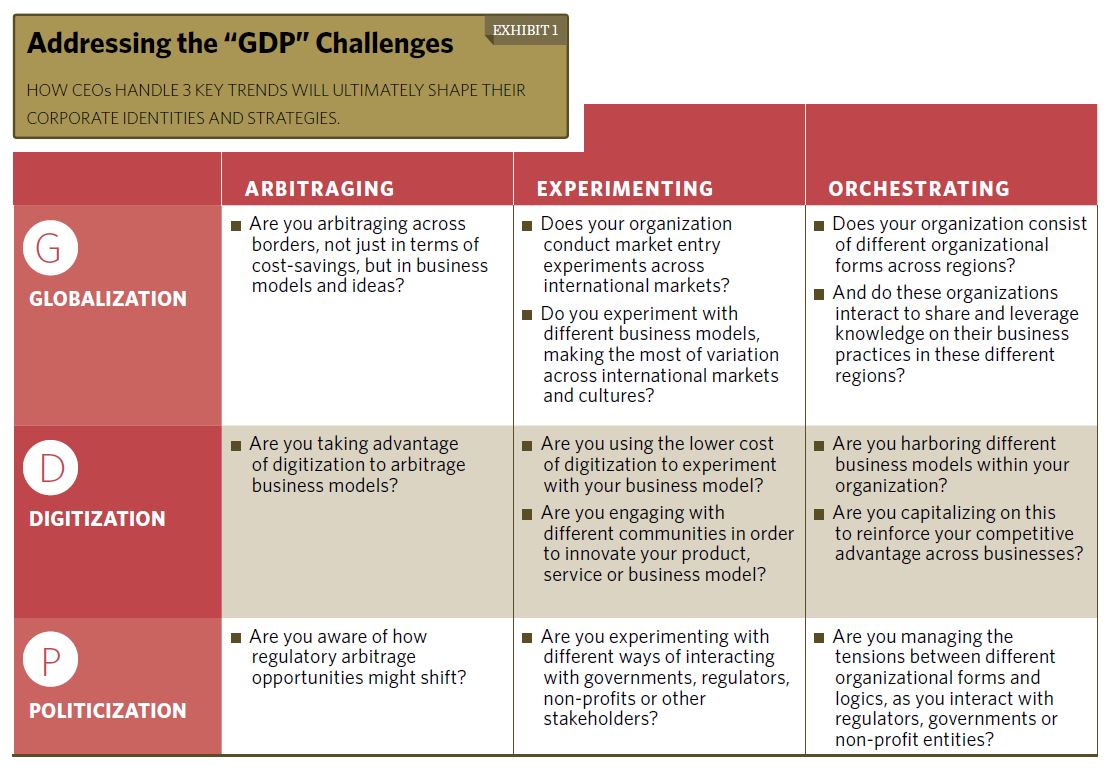

To confront Globalization, Digitalization and Politicization, leaders must rethink how they create, capture and sustain value.

By Fabrizio Ferraro and Bruno Cassiman

Over the course of the 20th century, gross domestic product (GDP) became the standard barometer of macroeconomic performance. Now, in the 21st century, CEOs face three trends impacting their performance: Globalization, Digitalization and Politicization. Think of these as “GDP” of an entirely different order.

This article develops a framework to think about these three challenges. We discuss how these challenges generate more uncertainty but also more opportunity for changing the rules of the game. The drivers of value creation and value capture are changing as:

- Emerging market multinationals are moving to the fore.

- Digital business models are reconfiguring the landscape.

- Innovation communities are transforming the way businesses interact with consumers and suppliers.

- Government and regulatory stakeholders are having an ever greater impact on the bottom line.

In light of this, CEOs will have to change how they manage — allocating resources differently, adopting a new mindset, and harnessing ambiguity as a source of competitive advantage.

Why the uncertainty?

When asked about their leadership challenges, CEOs typically mention the uncertainty and ambiguity regarding the future state of the world. But the real question is: What is driving this uncertainty?

There is no doubt that some forces are radically recalibrating the international business landscape. Technology is driving this change, but it’s not the only disrupter. There are other forces, economic as well as geopolitical.

The years since the 2008 global financial crisis have been marked by stop-start recoveries, trade wars and the rise of China. This makes choosing the right strategy for the right market a highly complex affair.

Let’s look at our three so-called “GDP” trends, which we believe are most impacting a company’s performance today.

1. Globalization, a mixed blessing

Globalization has proven to be a mixed blessing. The greater ease and faster movement of capital, goods and people across borders has opened up opportunities. It has facilitated the internationalization of operations as a means to reach and penetrate new markets with an adapted portfolio of products.

But it goes both ways. For every Western multinational profiting from opportunities in emerging markets, multinationals from emerging economies are doing the same in Western markets. For every executive delighting in the benefits of globalization, others are wringing their hands over the new competition.

2. Digitalization of products, business models and communities

More and more industries are seeing their core products and services being transformed by digital technologies. While this affords novel means of creating value, it can also be more difficult to capture the value created. Entry barriers are lowered, forcing incumbents to rethink their strategies.

This has given rise to a new generation of entities with markedly different business models. Amazon immediately springs to mind. But it’s not just traditional brick-and-mortar operations under threat. Even a wholly digital startup like Spotify that has shaken up the traditional business model of the music industry finds itself having to compete with other streaming services.

Digital business models may have eliminated transaction costs, but they haven’t cracked the code on other problems, like paying out more money for content, while getting less revenue per user. For creators and vendors of digital content, products and services, it isn’t just a question of capturing market share; it’s about translating it into solid, sustainable economic returns.

The other thing that digitalization has done is allow user communities to interact with the business like never before. External content creators provide creative inputs. In the case of open-source software development, innovation communities actually own the product and its creative process.

3. Politicization: accepting that everything is political

Another game-changing trend is the increasing politicization of the corporate world and the decline of the Westphalian Order – the belief in economic, political and legal sovereignty for individual nation-states, and non-intervention in other states’ affairs.

In the new global order, multinational corporations have a new role to play. Given that many companies have revenues that far outstrip the real GDP of most countries, they can no longer act as if they are disconnected from the world. CEOs will have to recognize their roles as political actors and assume the responsibilities that go along with that.

Granted, CEOs have always been aware of their public role, but this was rarely embedded into their responsibilities. More often, CEOs hid behind the identity of “private institution,” as if the “private” goal of maximizing profits never had any bearing on public life.

Now, with the blurring of the boundaries between public and private, CEOs need to step up and fully own their “politicized” roles, recognizing that they enjoy more economic, political and legal influence and power than ever before.

Back in 1957, the management scholar Philip Selznick wrote that CEOs should be “statesmen,” not just “administrators.” His words are even truer today: CEOs have little choice but to assume a more public, almost diplomatic role in brokering relationships between competing stakeholder demands and unavoidable social responsibilities.

How CEOs can deal with these shifts

1. The CEO as arbitrageur

Arbitrage is a common business practice that involves buying something in one place and selling it in another where it’s worth more. Which strategies can CEOs adopt to beat competitors through arbitrage principles?

- Globalization. To arbitrage across borders, CEOs judge global markets in terms of their potential to exploit differences — for example, buying low in one country and selling high in another. Pankaj Ghemawat argued this strategy needs to be taken further: besides offshoring and outsourcing, you can arbitrage business model ideas from one region to another, the way Tata arbitraged the lower cost of engineers in India to exploit business process outsourcing in Latin America. Another example is GE, which took low-cost ultrasound machines developed for use in rural regions in Asia, and commercialized them for ambulance crews in the United States at an 80% markdown from comparable products. This kind of “reverse innovation” is a lucrative form of market arbitrage.

- Digitalization. Rocket Internet arbitraged business models across different markets by taking a successful business model observed in the United States (Zappos) and replicating it in Europe (Zalando). While arbitraging business models like this is nothing new, digitalization has heightened its importance.

- Politicization. Regulatory arbitrage — taking advantage of tax breaks or more lenient legislation in other countries — is becoming increasingly difficult. For example, companies like Google, Apple and Facebook (Meta) are frequently fined for falling foul of the EU’s digital legislation. Google’s Larry Page was quoted in the Financial Times as saying he wishes he had been more engaged in policy debates in Europe as the EU’s stricter environment was having a real impact on his business. The lesson is clear: CEOs need to stay ahead of the curve on regulatory arbitrage and engage in policy debates; if not, the future will be decided for them. As political stakeholders demand tougher rules, it also means finding ways to position yourself to benefit from other countries’ standards, finding value while addressing stakeholder concerns.

2. The CEO as experimenter

To say CEOs need to keep experimenting with their business strategies is no surprise. However, experimentation is more urgent than ever, given that the “GDP” challenges are fast eroding whatever competitive advantage firms might have enjoyed in the past.

This demands leadership capable of creating the ideal conditions for experimentation to occur on a large scale.

In calling for greater experimentation, we are not saying that CEOs will no longer need to think strategically about the long-term future of the company. Quite the contrary, experimentation requires CEOs to develop a keen understanding of their competitive landscape, articulating possible futures, identifying the critical (hidden) assumptions that would catalyze those futures, and reacting nimbly to test those assumptions.

- Globalization. Companies may discover a successful strategy in one part of the world that can be rolled out across other regions. Adrian Caldart tells how Robert Iger chose to let Walt Disney Latin America manage all business lines (movies, videos, products, trips) through a single channel, rather than managing each separately as autonomous business units like in the United States. Such experimentation worked but, as one director commented, “Iger’s support was crucial.” This alternative approach was eventually adopted for the Indian and Chinese markets.

- Digitalization. The reduction of transaction costs lets CEOs test their assumptions by running low-cost experiments in ways previously unimaginable. You can run A/B testing and other user experiments on the features of websites, for example. One caveat: make sure your user experiments are done ethically; not like Facebook, when it manipulated news feeds to measure users’ emotional reactions without their knowledge.

- Politicization. Unilever’s former CEO Paul Polman experimented with traditional ways of doing business, based on a keen appreciation of his role and responsibility as a political actor on the world stage. Perhaps his most radical experiment was announcing that Unilever would stop issuing quarterly reports. Like Polman, CEOs need to experiment to strike a healthy balance between meeting business objectives while satisfying the needs of society at large — which may run them into trouble politically, as it did Polman.

3. The CEO as orchestrator

In terms of organizational design and capabilities development, the CEO must learn how to lead a complex organization that encompasses diverse activities, structures, processes and identities, while pursuing competing logics simultaneously.

- Globalization. The CEO needs to find new ways of bridging apparent divides and organizing multiple actors globally, both in a consistent manner and with profitable results. This requires CEOs to orchestrate hybrid organizations, capable of bridging and melding very different worlds. Part of biotech companies’ success is owed to their ability to blend practices borrowed from traditional university research settings with those of for-profit companies. Google did the same in its formative years. The major challenge is to balance the apparent conflict between the logic of science (the pursuit of knowledge) and the logic of business (economic viability).

- Digitalization. CEOs must become adept at orchestrating external sources of expertise, recognizing that the knowledge they seek may well lie outside their walls. CEOs must learn how to bring together collaborative communities in ways that contribute to tech development while also creating economic value that the company can capture. This is critical: digital orchestration is done not because technology makes it possible but insofar as it enables companies to achieve scale and profitability. The decision to keep operating systems and platforms open or closed must be strategic, not ideological. Being an orchestrator means knowing how to relate to external innovation communities, and how and when value can be captured by owning and managing critical parts of the process.

- Politicization. Orchestration is also necessary to address the politicization challenge, especially in assimilating the pluralistic demands of stakeholders. Engaging with all the different actors (for-profit, non-profit and governmental bodies) and developing collective solutions requires a hybrid mindset and disposition. CEOs cannot buffer themselves from this, delegating such responsibilities to Investor Relations or Public Relations. Instead, they must see stakeholder engagement as a crucial part of their role, and orchestrate the connections between them. Dow Chemical collaborated with an environmental NGO, The Nature Conservancy, to find solutions that jointly addressed business concerns and protection of the natural environment.

A plural identity that blends different logics

The challenges of Globalization, Digitalization and Politicization cannot be ignored. Apart from the challenges they raise, they also present timely possibilities for CEOs to move the organization forward.

But how can CEOs tell a consistent story, while at the same time leading organizations that are operating under different logics?

On a personal level, CEOs will need to become more comfortable with ambiguity, diversity, conflict and failure. Having a plural identity might help, similar to the way the British fashion designer Christopher Bailey once talked about being able to switch from nurturing the creative talents in the company to engaging in the intricacies of the business: “I can go from a big brainstorming meeting about tech or fabrics, then close that box and go into a meeting that is more structured about supply chains.”

At the organizational level, CEOs should seek to craft a vision that lends consistency to these actions, while also generating excitement among employees, inviting cooperation from stakeholders and creating a certain tolerance for failure and change.

All this will require drastic new ways of thinking about how we create, capture and sustain value.

A version of this article is published in IESE Insight magazine (Issue 23, Q4 2014).

This content is exclusively for personal use. If you wish to use any of this material for academic or teaching purposes, please go to IESE Publishing where you can purchase a special PDF version of “Three trends that will change how you manage” (ART-2640-E), as well as the full magazine in which it appears, in English or in Spanish.