IESE Insight

How companies can use power and partnerships to drive system change

Real change happens when business, policy and society move together. Here’s how leaders can move beyond isolated efforts and scale innovation for sustainable impact.

By Desirée Pacheco, Thomas J. Dean and Jacen Greene

A decade ago, many electric car makers struggled to compete in a world built for gasoline engines. Charging stations were scarce, battery costs were high, and government policies still favored traditional gas or diesel engines. Yet, by the end of 2025, 1 in 4 cars sold worldwide was an electric vehicle, with EVs forecast to represent 40% of the global car market by 2030. What’s more, several European countries have announced plans to phase out new internal combustion engines, with Norway on track to become the first country to go fully electric. EVs already outnumber fossil-fuel cars there. How did this change occur in such a relatively short period of time?

Real progress came only when automakers, battery manufacturers, energy providers and policymakers began working in tandem. Automakers created appealing new designs and adapted popular models to electric motors. Battery manufacturers scaled up production. Utility companies upgraded grids to meet rising demand. Governments introduced buyer incentives and invested in charging infrastructure. In response, consumer habits began to change. Simply designing a better car wasn’t enough — the entire transportation ecosystem had to evolve.

Our research, based on more than a decade of studying market dynamics and sustainability, confirms this pattern. Through in-depth interviews with transformational companies, we found that lasting solutions to social and environmental challenges rarely emerge from isolated actions. Instead, they develop through the coordination of multiple actors operating within interdependent systems.

Sustainable innovations offer much-needed answers to urgent global challenges, alongside compelling business opportunities. But their effective implementation often demands system-level change — something few leaders fully understand.

While technology can provide creative breakthroughs, its impact remains limited without collaboration across industries, governments and communities. To make a meaningful difference and unlock the full potential of innovations such as EVs, distributed energy generation, advanced batteries, carbon sequestration or regenerative agriculture, companies must go further: they must help reshape the broader systems in which they operate. That means shifting industry mindsets, incentives and structures to establish a new normal.

In this article, we describe how to influence key system stakeholders to scale sustainable innovations, which are essential for addressing global challenges today.

Understanding your stakeholders and how to influence them

To enable the dissemination of sustainable innovations within complex and multiactor systems, company leaders should be aware of two key factors:

- the type of power that their company has and how to harness it.

- the role of different stakeholders and how to target them.

Transforming a system often requires influencing key decision-makers — those who act as gatekeepers of technologies, solutions or policies. This includes securing the support of centralized stakeholders such as governments, competitors and suppliers, who individually control significant resources. For example, governments shape infrastructure and set the incentives or rules that define an industry, while suppliers may control access to materials critical for sustainable innovation.

Equally important are diffused stakeholders — end users and community members who, although lacking individual power, collectively determine whether innovations succeed. Unlike formal, resource-based relationships with centralized actors, interactions with diffused stakeholders rely more on social dynamics. The effectiveness of these relationships depends on trust, credibility and perceived social value, since they are informal in nature. Ultimately, these stakeholders are essential because they are the ones who adopt the products, services and business models that drive system change.

To scale their innovations, companies must learn to strategically influence both types of stakeholders. This begins with mapping the complex web of players who shape the market: centralized stakeholders such as policymakers, regulators, competitors, suppliers and NGOs, and diffused ones such as customers and community members. All of these groups are needed to create real change on a global scale.

Moreover, every company wanting to drive system change holds unique types of power that need to be considered in the process. And the way a firm engages with each stakeholder depends largely on the type of power it holds.

Power dynamics: legitimate, coercive and referent

There are five different types of power, as identified by social psychologists John French and Bertram Raven in their influential 1959 study, “The bases of social power.” For the purposes of this article, we will explore three of them:

- Legitimate power, the formal right to make demands, stems from a company’s social position and its standing with the public.

- Companies may also possess coercive power, which enables them to force compliance or punish others for noncompliance.

These two forms of power are often associated with organizational size, as both coercive and legitimate power tend to increase as a company grows.

- Firms may also exercise referent power, which is earned through respect and admiration, as others with shared values perceive the company to be more authentic.

Hence, a company’s size can determine its degree of legitimate or coercive power, while its perceived authenticity regarding sustainability can shape its referent power over others.

Larger companies, with greater legitimate and coercive power, are better positioned to influence centralized stakeholders, as their demands are more likely to be addressed given their control over key resources.

On the other hand, companies perceived as more authentic in their sustainability initiatives and messaging may be better positioned to influence diffused stakeholders, who place greater value on trust and social desirability.

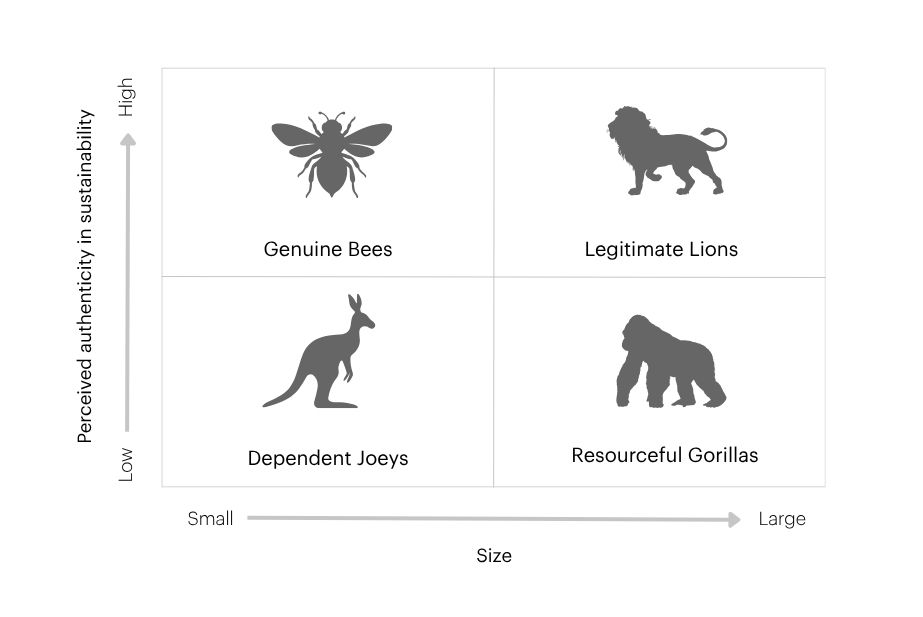

We developed a framework for identifying strategies to influence stakeholders based on the size and perceived authenticity of innovators seeking system change. Each firm faces different constraints and opportunities, requiring it to tailor its approach to each stakeholder.

To make this framework memorable, we use the metaphor of animals in natural ecosystems to highlight the different roles companies can adopt when seeking transformational, system-level change.

A framework for identifying strategies to influence stakeholders

Dependent Joeys: small and unknown, needing support

We start small with Dependent Joeys. A joey is a newborn kangaroo, extremely small and underdeveloped, so it has to stay attached to its mother for a while before it is ready to venture out on its own.

Likewise, in this category, we can think of smaller organizations with limited legitimate, coercive or referent power. Unable to influence key stakeholders on their own, they often depend on partnerships with like-minded entities, trade associations or coalitions for support. Collectively, they can grow in power to eventually influence the broader system.

Many social and environmental NGOs fit this description.

In research we have done with colleagues on the early days of wind and solar power, we found that, in the absence of strong economic arguments, regulation and government subsidies, many small nonprofits and social enterprises banded together to lobby and engage in public-private partnerships. Together, they developed specialized technical knowledge that could be used to build a business case for renewables.

This generated a self-sustaining circle, with smaller players connecting with a broader base of activist users, which helped create market-based incentives and pushed clean energy higher up the public agenda.

Working in collaboration with multiple stakeholders lent credibility and helped grow a bigger movement, so the small “joeys” could eventually leap ahead.

Resourceful Gorillas: big and powerful, handle with care

Next are the Resourceful Gorillas: large and powerful organizations that may lack perceived authenticity in their environmental or social initiatives. Owing to their size, they can exert significant coercive influence over suppliers and regulators. However, to compensate for their limited referent power and to build credibility with the public, they often rely on partnerships with trusted actors, such as NGOs, to convey more authentic sustainability messages.

Walmart is a case in point. As the world’s largest retailer by revenue, Walmart’s massive scale allows it to exercise coercive power in negotiation with manufacturers and other suppliers, forcing them to comply with its low-cost demands or risk being replaced. Also, as the largest private employer in the world, it has a huge impact on employment and wage trends. It has put many small, local, mom-and-pop competitors out of business. And research shows that, much like Amazon, when Walmart is the main employer in town, wages stagnate.

But Walmart has been working hard to boost its authenticity. Shortly after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Walmart’s then-CEO Lee Scott gave a speech in which he admitted:

“We have received our share of criticism over numerous issues, not the least of which is our size… To better understand our critics and Walmart’s impact on the world and society, we spent a year meeting with and listening to customers, associates, citizen groups, government leaders, non-profit and non-government organizations, and other concerned individuals.” He signaled a change of direction.

“Walmart, believe it or not, committed to becoming regenerative, with a plan based directly on the work of the environmentalist Paul Hawken,” said John Elkington, a world authority on corporate responsibility and sustainable development, speaking at an IESE Global Alumni Reunion on SustainAbilities.

Sometimes bigger can be better — if you use your giant resources to good effect. Walmart’s sustainability effort has been helped by partnering with responsible suppliers as well as with Conservation International, the Environmental Defense Fund, The Nature Conservancy and the World Wildlife Fund, among other authentic players.

“Due to our size and scope, we are uniquely positioned to have great success and impact in the world, perhaps like no company before us,” said Scott.

Genuine Bees: small but highly authentic

Now let’s consider organizations that are perceived to be more authentic when it comes to their sustainability credentials, but they lack coercive power owing to their smaller size and scale. We call these Genuine Bees. Many certified B Corps fall into this category — enterprises that are for-profit but also have a strong social and/or environmental mission.

These types of organizations may not wield much direct, coercive influence over large corporations or government policy. However, they command a lot of referent power. Consumers tend to trust and respect them. This can inspire grassroots movements like the fair-trade movement. While fair trade started among niche players, larger stakeholders were eventually pushed to begin offering fair-trade alternatives as consumers demanded more equitable products and services.

One such example is Tony’s Chocolonely, a Dutch chocolate brand known for its long-standing commitment to ending slave labor in the cacao industry and paying farmers the true price. Compared with a large multinational chocolate maker like Nestlé, Tony’s cannot compete, as Tony’s head of sustainability, Chris Oskam, explained during a talk at IESE:

“Because we pay more to farmers, our cost base is higher, which of course affects our competitiveness because it puts us at a different price point. To overcome that, we have to do other things to set ourselves apart.”

Writing about Tony’s in IESE Insight, Christopher Marquis recommended working collectively. Through the Open Chain initiative, Tony’s succeeded in getting other producers to pledge to end forced labor and child labor within their industry. This saw big brands from Aldi to Ben & Jerry’s (owned by Magnum, a Unilever spinoff) committing to increase what they paid farmers — a win for the Genuine Bees.

The Genuine Bees’ other secret weapon, compensating for their limited coercive power, is their ability to generate disproportionate media attention through creative marketing campaigns. In fact, a study by one of us on small, sustainable apparel brands found that, despite their tiny market shares, nearly half of all U.S. mainstream media articles on sustainable apparel over a 10-year period featured smaller brands.

The takeaway is that small but highly authentic firms can still generate a lot of buzz — a powerful reminder of the reach and relevance of referent power.

Legitimate Lions: the double advantage of being big and authentic

The final category is Legitimate Lions. These companies combine size with high public trust. They enjoy both legitimate and referent power, allowing them to drive change with both centralized and diffused stakeholders.

For instance, the large outdoor sports clothing company Patagonia uses its brand to rally customers around environmental causes while also pressuring suppliers to meet sustainability standards. This, in turn, leads consumers to identify even more strongly with the brand, resulting in Patagonia being consistently ranked as one of the most respected brands of all time.

Despite having the double advantage of being a large company and being perceived as authentic, even Legitimate Lions like Patagonia can benefit from collaborating with others — maybe to access a larger pool of Resourceful Gorillas, or maybe to cultivate an even more authentic image with Genuine Bees.

Dependent Joeys, with their small local followings and lesser-known reputations, could have a bigger impact if they chose to partner with Legitimate Lions.

Speaking at IESE on his experience of working with Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard, Dean Carter gave numerous examples of how the company partnered with stakeholders in pursuit of its mission “to save our home planet.” Patagonia gives a percentage of its revenue — including up to 100% of Black Friday revenue — to a variety of environmental groups dedicated to preserving and restoring the natural environment. And when Chouinard made Forbes’ rich list, he set up a trust and nonprofit to get him off that list by giving his money away.

“Now, all the profit from Patagonia, after paying expenses and people, will go to small, grassroots efforts to save the planet, around the world, forever,” Carter said, underscoring Patagonia’s commitment to use its sizable resources to help drive system change through other authentic partners.

Harness collective power to scale innovation

System change rarely happens on its own — it emerges when mindsets, incentives and policies shift in concert across society.

Companies that learn to harness their power to shape these broader systems are far better positioned to earn public trust and scale their innovations. To do this effectively, they must develop strategies that either leverage the forms of power they already possess or compensate for the ones they lack.

This often involves partnering with stakeholders who hold complementary forms of power — whether industry peers or civil society organizations — to unlock parts of the system that are essential for their innovations to spread.

In the context of sustainability, companies with lower referent power, like Resourceful Gorillas, must collaborate with actors who have high referent power, such as Genuine Bees or Legitimate Lions, to influence diffused stakeholders.

Conversely, companies with low coercive power, like Genuine Bees, can benefit from the support of Resourceful Gorillas to influence centralized stakeholders.

By engaging in this kind of systemic collaboration, companies can address urgent global challenges while also building enduring competitive advantage.

MORE INFO:

Some of the ideas contained in this article were shared as part of the session “Integrating sustainability into your business model: building it from the ground up or evolving existing practices,” delivered during the 2025 International Women’s Entrepreneurial Challenge, hosted by IESE Business School, CaixaBank, Spanish Chamber of Commerce and Barcelona Chamber of Commerce.

“Social movements and entrepreneurial activity: a study of the U.S. solar energy industry” by Desirée Pacheco and Theodore Khoury. Research Policy (2023).

“The coevolution of industries, social movements and institutions: wind power in the United States” by Desirée Pacheco, Jeffrey York and Timothy Hargrave. Organization Science (2014).

“Escaping the green prison: entrepreneurship and the creation of opportunities for sustainable development” by Desirée Pacheco, Thomas J. Dean and David Payne. Journal of Business Venturing (2010).

Desirée Pacheco acknowledges the support of grant PID2020-113259RA financed by AEI/MCIN/10.13039/501100011033.

This article is included in IESE Business School Insight online magazine No. 171 (Jan.-April 2026).

READ ALSO:

How social movements give renewables a boost

Go solar: How social movements influence industries and help them grow

How ethical is your supply chain? Lessons from Tony’s Chocolonely

How brands can help people become their authentic selves